This essay describes an ongoing collaboration between multiple colleagues in disparate institutions and offers the authors an opportunity to reflect on the successes and challenges of the cooperative project. In the spring of 2020, conservators, conservation scientists, and curators from the United States and Italy began a collaborative research project to compare the three earliest and most complete surviving decks of illuminated Italian tarocchi cards, known collectively as the Visconti-Sforza decks. These decks of handheld cards were created in the middle of the fifteenth century to play trick-taking or gambling games and are generally attributed to Bonifacio Bembo and his workshop. One deck is located at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven, CT; one is at the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy; and one is divided between the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo, Italy, and a private Italian collection. The rich color palette and intricately tooled gilded backgrounds of the cards have been the subject of endless fascination and numerous art historical studies, but until now they have not undergone in-depth technical analysis. A discussion between two colleagues about the materials used to create the cards grew into a multi-institutional endeavor fueled by a shared enthusiasm to fill the knowledge gap on the technical production of Italian tarocchi cards. The goals of the project are to identify and compare the composition of the decks, to emphasize their materiality in the art historical record, and to increase cooperation between professionals in the cultural heritage field. This essay explores the genesis and logistics of the project, the historical background of the decks, and the main findings on the cards’ materials and techniques to date.

I. Tarocchi Teamwork: An International, Multi-institutional Collaborative Research Project

- Francisco H. Trujillo

- Federica Pozzi

- Marie-France Lemay

- Richard R. Hark

Introduction

One of the raisons d’être of art museums, conservation, and conservation science is to convey how works of art are created and produced. This essay describes a collaborative research project that aims to fully understand how three sets of similar, yet ultimately distinct, decks of tarocchi cards were made between 1441 and 1458 in and around Milan, Italy. The decks are held in museums and libraries in the United States and Italy. There are several factors that make the decks compelling art objects. The decks’ rich color palette and intricately tooled and gilded backgrounds engender an immediate visual impression and pose questions as to their construction. The decks combine three artistic techniques of the mid-fifteenth century—fresco, panel painting, and manuscript illumination. However, they are unique in their production—they are handheld works of art illuminated on adhered layers of paper, essentially the first card stock, and are elaborately decorated with colorful characters over gilded backgrounds with extensive punchwork.

The project began as a comparative study of decks between two United States collections, but expanded organically into a collaborative, multi-institutional, international project that benefited from expert and varied points of view. The main research questions centered around the exact composition of the cards including substrate, underdrawings, pigments and colorants, gilding, and punchwork, and how this informs the date of their creation and their possible creators. Additional questions were raised as initial data were interpreted and analytical techniques were expanded. The aim of this essay is to elucidate the distinctive circumstances surrounding this collaborative study, provide a succinct overview of the analytical techniques and results, and underscore the key factors contributing to the success of the collaboration among multiple institutions and participants.

The success of the project pivoted on the ability of the participants to review data via online meetings and iterative in-person viewings of the decks of cards. The combination of online and in-person discussions provided the means to think creatively as a group and to advance the goals of the project. The project and its members benefit from working in supportive research environments that emphasize art historical and technical studies. Without strong, long-term institutional commitment, collaborative, in-depth, multiyear projects such as this study of tarocchi cards could not realistically take place.

Tarocchi defined and project genesis

Tarocchi is the Italian term for playing cards used in a trick-taking game that makes its first appearance during the first half of the fifteenth century in Northern Italy.1 Little is known of the early history of tarocchi cards or of early playing cards for that matter. References to playing cards are found in late fourteenth-century archival records from Germany, Italy, Catalonia, Belgium, and France, with the earliest reference dated 13712 and the earliest mention of tarocchi cards from 1440.3 These records are largely sermons condemning playing cards as immoral or laws regulating or forbidding their use,4 although tarocchi—initially a trick-taking game that required strategy reserved for the court or the elite—seems to have been spared regulation and prohibition. Furthermore, primary sources suggest that tarot cards were not used for divination purposes until the end of the eighteenth century.

There are no surviving examples of playing cards from that period, and archival records offer little insight into early methods of production. Scholars have suggested that the first decks were most likely painted but that with their popularization and the subsequent growth in demand, the production must have shifted to woodblock printing—which allowed for the impression of several cards on one sheet of paper—followed by hand coloring with or without the aid of stencils. This seems like a reasonable assumption given that the appearance and development of playing cards coincides with the development of woodblock printing and the increasing availability of paper in late fourteenth-century Europe.

The tarocchi deck grew out of and is an expanded variation of early decks of playing cards. While early decks, like our modern decks, usually contained fifty-two cards, a conventional tarocchi deck contains seventy-eight cards: fifty-six pip and court cards divided into four suits—Cups, Batons/Staves, Swords, and Coins—and twenty-two trump or tarocchi cards consisting of figures such as the Emperor, Pope, Death, and the Hanged Man.5 The three oldest and most complete surviving examples of tarocchi decks are known collectively as the Visconti-Sforza decks: the Visconti di Modrone deck6 in the Cary Collection of Playing Cards at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT; the Brambilla deck at the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy; and the Visconti-Sforza deck, also known as the Colleoni or Colleoni-Baglioni deck, which is divided between the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, the Accademia Carrara and the private Colleoni collection, both located in Bergamo, Italy (Fig. 1).7 A complete deck no longer exists in any of the holding institutions: Yale has sixty-seven cards, Brera has forty-eight cards, and the Morgan/Carrara/Colleoni collections together have seventy-four cards. There are approximately three hundred and forty extant illuminated tarocchi cards in worldwide collections.8 Together, the three Visconti-Sforza decks account for more than half of the existing cards.

Created between 1441 and 1447, the Yale and Brera decks were likely commissioned by Filippo Maria Visconti, duke of Milan from 1412 to 1447. The Yale pack may have been produced for the marriage of his daughter, Bianca Maria Visconti, to Francesco Sforza in 1441. The Morgan/Carrara/Colleoni deck, completed in 1456–1458, is thought to have been commissioned by Francesco Sforza, Filippo Maria Visconti’s son-in-law and successor as duke of Milan. The three decks have been generally attributed to Bonifacio Bembo and his workshop. Bonifacio Bembo was an artist from Cremona, Italy, known for his multimedia work in fresco, panel painting, and manuscript illumination. The most recent art historical scholarship suggests the Yale deck might be the work of Bonifacio’s older brother, Andrea. The Brera deck is attributed to the Bembo workshop.9 Unlike their later printed and hand-colored counterparts produced for the masses, the Visconti-Sforza tarocchi—painted by established artists of the time or their workshops, using some of the finest materials available such as lapis lazuli and red lake pigments, and gold and silver leaf applied to backgrounds subsequently filled with elaborate ornamental punchwork (no doubt a time-consuming process, given the number of cards)—were commissioned by and created for the elite. Their large size10 and relatively good condition, considering their age, make it hard to imagine that they were ever used as playing cards.

The tarocchi research project began on the sidelines of the installation of the 2016 exhibition The World in Play: Luxury Cards 1430–1450,11 to which cards from the Yale and Morgan decks were lent. A conversation between Marie-France Lemay and Frank Trujillo, conservators from Yale and the Morgan, respectively, prompted them to inquire as to the exact composition and method of creation of the decks. While there exists, in Italy in particular, a large body of published historical and art historical research that focuses on attribution and dating of the three decks, they have not been the subject of any in-depth material and technical analysis. The body of technical research on panel paintings is abundant, and that of manuscript illumination has seen a significant growth in recent years thanks to the development of noninvasive or minimally invasive analytical techniques, but there is a distinct dearth of published research on illuminated tarocchi cards.12 The relatively small number of extant cards in private and public collections13 and the challenges many institutions face to access the equipment and expertise necessary to undertake such technical analysis is no doubt partially responsible for this. A fortuitous second meeting in late 2016 at the “Manuscripts in the Making: Art and Science” conference14 was a fitting backdrop to a conversation where a comparative study of the materials and techniques of the Yale and Morgan decks was discussed, but it would be a few years before the conversation resumed.

In late 2018, a small interdisciplinary team consisting of a paper conservator, a paintings conservator specializing in early Italian panel painting, three conservation scientists, and the curator of Yale’s Cary Collection of Playing Cards began working together on a technical study of their deck. The establishment of the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH) in 2011, as well as the availability and access to scientific equipment and the expertise of conservation scientists on campus, made it possible for conservators to engage in a study of the materials and techniques used to create Yale’s tarocchi deck. The joint purchase of a Bruker M6 JETSTREAM scanning X-ray fluorescence (XRF) system between IPCH, Yale University Library, and the museums at Yale provided further impetus to pursue this research.

In late 2019, Yale Library and IPCH invited conservators from the Morgan to Yale University to discuss the technical study on their deck. Soon after, conservators from the Morgan organized a reciprocal visit with Yale colleagues to view the Morgan’s deck and to discuss the viability of a comparative study of the decks at Yale and the Morgan. Conservators from the Yale Library and conservation scientists from IPCH met with conservators and curators in the Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts Department from the Morgan and conservation scientists from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Network Initiative for Conservation Science (NICS).15 The main goal of NICS is to share the Met’s resources, expertise, and state-of-the-art scientific research facilities with a core group of partner institutions in New York City, providing them with the required scientific support to conduct technical studies of artifacts in their collections free of charge.

The assembled conservators and conservation scientists agreed that a technical and material study of the Yale and Morgan decks would be of interest to all parties. The meeting provided the first instance of what would become a regular feature of the study, namely, the benefits of group meetings in the presence of the cards. The opportunity to discuss the art objects with a multiplicity of viewpoints and expertise would prove invaluable throughout the tarocchi study. During this initial meeting, the laminate paper structure of the cards was of immediate interest to the group. Areas of loss at the edges of the Morgan cards revealed evidence of adhesive between paper layers, which led to impromptu ultraviolet examination and photography and, later, scientific analysis to attempt to identify the adhesive.

At its outset, the project’s focus was to identify and compare the materials and techniques used in the creation of the Yale and Morgan tarocchi decks based on the results of visual examination and scientific analysis. Several fundamental questions the team wished to investigate were outlined: how were the paper supports constructed? Is there any evidence of preparatory composition or underdrawings? What pigments and binders enter into the composition of the ground, bole, and paint layers? What causes the different tonalities in the metal leaf backgrounds? What are the similarities and differences in materials and techniques between the two decks? What do those similarities and differences tell us about the production of the cards? It is crucial to emphasize that it was the conservators and conservation scientists who formulated these initial technical questions, which were then further refined with curatorial colleagues.

As the team discussed the scope and goals of the project, an interesting conversation sparked around the seemingly hybrid nature of the cards, which appear to borrow and combine materials and techniques from manuscript illumination, panel painting, and fresco. At first glance, parallels could be made with panel painting practice in the use of a rigid support and paper borders that could be likened to an engaged frame, while the small dimensions of the cards, the paper substrate, and the painted borderlines were reminiscent of manuscript illumination practice. This intersection seemed like fertile ground to investigate and explore further. Could we pinpoint the use of specific painting practices in the cards by comparing our results to contemporary painting practices described in well-known historical treatises or in published research on fresco, manuscript, and panel painting? Could an in-depth technical study of the tarocchi serve as a case study in the cross-pollination of artistic and workshop practices in Renaissance Italy? Our investigation is ongoing, but we hope that our scholarship will shed light on these questions.

Furthermore, the impact of this study would be magnified by the decks’ wide and diverse population of users. The decks are regularly requested on loan, and by researchers and readers at the Morgan and at Yale, where the Cary Collection of Playing Cards is widely known for its holdings. Curators and conservators at each institution frequently engage with enthusiasts and experts who have precise material and technical questions about the cards, many of which are difficult to answer because of the lack of any previous technical study. The cards appeal to a broad audience ranging from the general public to artists, art historians, professional and amateur tarot card readers, as well as playing card scholars and enthusiasts—each drawn to different aspects of the cards: aesthetic, esoteric, historical, or material. This broad appeal is reflected by their inclusion in several exhibits over the years and in publications, websites, and forums entirely dedicated to the history of playing cards, where the three Visconti-Sforza decks are the frequent focus of lively discussions and debates.16 The longest running of these debates is perhaps the one art historians and playing card scholars have been engaged in for decades surrounding the attribution and dating of the three decks, a discussion that has relied mainly on the interpretation of stylistic, historical, and art historical evidence. Through the dissemination of the results of our research, we hope to feed the discussion with fresh, valuable data that will emphasize the materiality of the cards in dialogue with the work of historians and art historians, generating further exchanges among professionals in the cultural heritage field.

While the project was originally spearheaded by an interdisciplinary team from multiple institutions in the United States, there was a strong interest from the beginning to include the cards from Brera and the Accademia Carrara in the comparative study. The decks’ links to the Visconti family, the time and place of their creation, the debates surrounding dating and attribution, and the cards’ material, visual, and stylistic similarities have resulted in a natural tendency from experts and scholars to group the three decks together in their scholarship. The possibility of including the decks from Italian collections became a reality in the second half of 2021, after NICS scientist Federica Pozzi moved to Italy to take on a new role as Head of Scientific Laboratories at the Centro per la Conservazione ed il Restauro dei Beni Culturali (CCR) “La Venaria Reale,” one of the three strategic poles for the training, study, and research on cultural heritage in the country, located just outside of Turin.

Several factors contributed to promoting this project to the management of the institutions involved. At the CCR, for instance, all research is typically funded through European grants or specific sponsors. Despite the unavailability of financial support for the tarocchi project, the center’s secretary general foresightedly agreed to pursue this collaborative research because of the exceptional relevance of the artifacts under study and the prestigious international partnerships that the project would entail. At Yale and the Morgan, research initiatives into the technical composition of collection material, including collaborative work with other collections, are encouraged and supported within the working structures of the respective institutions. The circumstances for colleagues in other museums or institutions may not be as conducive to a research initiative on the scale of the tarocchi project, but the authors’ goal is to foreground the idea that a project that is of mutual interest to like-minded professionals can be realized, sometimes through sheer determination.

Development of a comparative and collaborative project

Everyone involved—conservators, conservation scientists, and curators—has given and continues to give much time, energy, and expertise to this endeavor. The research project began as a comparative study of decks from Yale and the Morgan, but grew into something larger and more interesting—a collaboration among peers with a shared interest in learning as much as possible about the creation of the cards using all analytical techniques at their disposal. The research team eventually developed a moniker, Team Tarocchi, reflecting the shared enthusiasm among members for studying the decks.

Each close viewing of the decks among team members engendered new questions about just how, exactly, the cards were made. The close viewing of the cards in each other's company provided a sounding board for different points of view, different theories of the cards’ creation, and new ideas on how to answer evolving questions using analytical techniques and art historical research. Group viewings involved arraying the decks of cards, allowing for a different perspective with which to regard the cards: rather than examining one card under a piece of analytical instrumentation, multiple cards were set side by side and patterns of production emerged. From this close examination and discussion, the use of green or red glazes over metal leaf was documented and highlighted for analysis, the different borderlines between pip, court, and trump cards were discovered, and dissimilarities in the use of models in the Yale and Morgan decks observed. Each group member brought their particular point of view or interest to the viewings, a productive approach in which to regard the many cards in each deck. While the decks piqued everyone’s curiosity, the ability to speak with each other regularly in person and through Zoom meetings was a welcome change from the imposed solitude of the COVID-19 pandemic. The group members worked from home for months beginning in March 2020, so having such an interesting research project to share in the spring of 2021, and the means to undertake it, felt less like work as usual and more like kismet—proof that things in the world were settling back to normal.

As data were acquired and interpreted, the group shared and discussed the material and technical insights with each other during virtual meetings and hypothesized about the successive steps involved in the creation of the cards. In-person meetings at each collecting institution, in the presence of the cards, were crucial to discussing and supporting scientific findings with visual analysis and developing a production model for the cards. For instance, close inspection of the Accademia Carrara tarocchi cards during a recent trip to Italy by some of the team members was crucial to establishing similarities and differences from the remaining portion of the deck held at the Morgan. While examining the cards together, conservators and scientists noticed extensive use of green glazes, not present in the Morgan cards, for some of the figures’ headdress feathers and gloves; based on this joint observation, a decision was made to conduct systematic, in-depth analyses of the organic materials. The team also detected some peculiar features on one of the cards, the three of staves, under magnification: this prompted a series of in-depth scientific investigations, carried out in the following weeks, to ascertain whether the card could have been made by a different hand at a later date. A visit to the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, during the same trip, provided the team with an invaluable chance to examine the Brera deck in person; on this occasion, conservators identified a subset of cards, based on their observed features, for in-situ scientific analysis. As is often the case, interpretation and discussion of findings would result in fresh new questions, prompting the team to reevaluate results and hypotheses or to seek tools or techniques that could answer these new questions. The current breadth of the collaboration is made visible in Fig. 2.

Collaboration and isolation: Scientific testing, logistics, and timeline during a global pandemic

In January 2020, conservators from the Morgan submitted a research proposal to study a selection of their tarocchi cards to NICS. Over its initial six-year term, NICS accommodated all requests from partners in the New York City museum community. Work carried out through this program included both fully fledged research projects with a strong scientific component, broad scope, and demonstrated relevance in the fields of art, conservation, and science, and analytical service (i.e., routine analysis aiming to address specific questions typically related to conservation treatments). Proposals received by NICS staff revealed, for the museums involved, different priorities and approaches: while some mostly submitted service requests, others prioritized more comprehensive, well-contextualized projects.17 Belonging to the second group, the Morgan’s proposal to NICS involved an in-depth technical analysis of select cards, focusing on various aspects of their materiality, such as paper support, preparatory composition and drawing, bole, type of metal leaves, ornamental tooling, pigments and binders, and respective techniques of application. The wealth of information gathered from this project would complement data from the concurrent study of the Visconti di Modrone deck at Yale, contributing to the ongoing conversation and body of research. The intrinsic value of the NICS program is the mobility of some of its analytical equipment, which allows conservation scientists to conduct analysis in situ at various collaborating institutions.

The onset of restrictions from the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, however, presented an unanticipated hurdle and paused the research project, as museums across the United States closed their doors and staff received an indefinite mandate to work from home. Mandated health strictures precluded travel of personnel between the Met and the Morgan until late spring of 2021. During the winter of late 2020 and early 2021, Yale’s scientists suggested sending cards from the Morgan to IPCH until NICS could resume analytical projects.

Conversations with IPCH led to the shipment of seven Morgan cards for XRF and Raman analysis, which occurred from April to July of 2021. The seven Morgan cards selected matched similar cards in the Yale deck. Timothy Young, curator for the Cary Collection of Playing Cards at Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscripts Library, kindly offered to cover the shipping costs using resources available through the Cary Fund.18 Almost simultaneously, the resumption of activities with NICS was possible if the cards could be transported from the Morgan to the Met. Sixteen cards, selected by Morgan conservators based on potential interest as revealed through visual examination, were delivered to the Met in May 2021. Transportation of the Morgan cards to IPCH and to the Met for scientific analysis was arranged thanks to the invaluable cooperation of registrars from all institutions.

A timeline illustrating the international and collaborative nature of the project, along with the different phases of work, is shown in Fig. 3.

Scientific testing of the cards at the Met initially involved a thorough investigation by means of noninvasive techniques, such as optical microscopy, point and scanning XRF, X-ray diffractometry (XRD), micro-Raman, and hyperspectral imaging. While extremely rewarding, especially after a prolonged period of isolation, collaborative work required careful planning due to the extant guidelines for safe working operations to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Precautions included staff rotation to limit the number of personnel working in the laboratory at one time, wearing masks, and social distancing. Met scientists carried out most of the noninvasive analysis between May and June 2021, carefully assisted by conservation colleagues from the Morgan. This effort was informed by the previous work carried out at IPCH on both Yale and Morgan cards. To tackle specific materials-related questions that could not be addressed by noninvasive analysis—such as the unambiguous identification of organic colorants, paint binders, and glazes—the team agreed to pursue selective sampling. Suitable sites for sample removal were carefully selected by conservators and scientists by jointly examining the cards under magnification. Wherever possible, samples were taken from preexisting areas of loss, following the principle of minimal invasiveness.

Samples were analyzed by means of benchtop techniques such as Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) over the course of about a week. Before the cards were shipped back to the Morgan in July 2021, several viewings were arranged in the Met’s Department of Scientific Research for conservators and curators from both institutions. During this time, Yale team members continued to carry out noninvasive spectroscopic analysis of the cards. All the extant court and trump cards from the Yale deck (twenty-eight cards) and nine pip cards were scanned using XRF, and many of them were carefully examined and imaged with a stereomicroscope. In this case as well, minute samples, representative of various glazes and colored paints, were removed for micro-invasive analysis with the techniques mentioned above.

Work in Italy also developed as a complex partnership among several institutions, requiring significant communication efforts with varying levels of formality and a manageable load of bureaucracy. While serendipity often plays a role, especially within large-scale, collaborative projects such as the one described here, it is only through meticulous organizing at each step that one can pave the way for a successful outcome. In the summer of 2021, initial contacts were made via email and phone with the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo and the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, with which the CCR had longstanding collaborations in place regulated by formal agreements. Between July and December, letters of invitation were sent to the directors of both museums to formalize their participation in the research project, which would entail making the Visconti-Sforza tarocchi decks in their respective holdings available for technical analysis. In February 2022, after signing a loan agreement, a selection of fifteen cards from the Accademia Carrara was shipped to the CCR laboratories for in-depth scientific investigation using portable and benchtop equipment; samples were also collected for a micro-invasive characterization of materials that would be otherwise difficult to identify, such as the organic red lakes, binding media, and translucent glazes.

In April 2022, after international travel restrictions had been lifted, a group of conservators and scientists from the Morgan, Yale, and the Met spent two weeks in Venaria Reale to join CCR colleagues in the examination of the Carrara deck from Bergamo (Fig. 4). During that time, the team also traveled to Milan to inspect the Brera deck. Although the Carrara and Morgan cards are from the same deck, they had not been seen previously by curators or conservators from the Morgan.

The opportunity to see the Carrara cards in person allowed team members to compare and contrast the Morgan cards and address some questions that had been raised about their level of deterioration. It became clear that at least one Carrara card was made at a later date and from different pigments than the rest of the Carrara/Morgan deck. The Brera deck had previously only been seen by two team members, Federica Pozzi and Elena Basso, but the opportunity to see the cards again with more members of the team and incorporate the group’s observations into the study was informative, since after viewing the Carrara and Brera cards it became apparent that the Yale and Brera decks were much more similar to each other than to the Morgan deck. This may correlate to the dating of the decks and their attribution to different members of the Bembo family.

The Accademia Carrara deck was shipped back to Bergamo in June 2022, after the analytical campaign was completed. As Brera cards were deemed too fragile to be removed from their own housing and transported to the CCR, a decision was made to arrange an in-situ, noninvasive analytical campaign in Milan, which would enable data acquisition while avoiding concerns regarding the objects’ conservation state.

In June and October 2022, CCR scientist Federica Pozzi spent five days at the Pinacoteca di Brera with portable instrumentation to carry out technical analysis of their tarocchi deck. From a logistical perspective, the identification of suitable dates for conducting these investigations posed a great challenge due to the need to coordinate three different teams of experts (from CCR, Brera, and Bruker Nano Analytics), while fitting into the museum’s busy schedule of activities. Analysis with compact instrumentation, such as videomicroscopy and handheld Raman, was performed in the Pinacoteca’s Cabinet of Drawings and Prints. Bulkier analytical equipment, however, could not fit in there due to space constraints and concerns related to radiation protection; because of that, a decision was made to conduct the remaining phases of the scientific investigation in a more spacious laboratory. Radiation protection regulations in Italy require following a series of safety procedures when moving X-ray systems to prevent dangerous exposure to ionizing radiation: these include notifying the institution’s radiation protection expert of the program of activities, providing relevant documentation, such as floor plans regarding the rooms where the instruments will be installed and used, and accurately enclosing the working area.

In addition to using CCR equipment and a hyperspectral imaging camera belonging to the Met, which was shipped to Venaria Reale prior to the April international visit, the analysis of cards from Bergamo and Milan relied on the collaboration of colleagues from Bruker Nano Analytics. The company made available to the research team a portable XRF spectrometer (Elio) and an integrated XRF and hyperspectral scanning system (IRIS), along with its engineers’ technical expertise. This real-time collaboration between conservation scientists and vendors is fruitful to both parties. Scientists gain use of equipment they may not otherwise possess, while vendors increase their understanding of the types of analyses undertaken by the art conservation field. An additional advantage for vendors is the production of marketing material: in this case, a short video, which promoted one of the Bruker instruments, was filmed while the cards were being analyzed at the Pinacoteca di Brera, and a dedicated post featuring the ongoing activities and partnership were shared on the company’s social media.

The in-situ investigations carried out in Venaria Reale and Milan required considerable joint efforts to define the most suitable experimental settings in terms of acquisition time and the resulting resolution of the images and spectra. Especially in the case of Brera, finding the best compromise between accurate data collection and the need to gather as much information as possible within the limited time available at the Pinacoteca was key to the success of the analytical campaign.

Providing comparable data with the instrumentation available at each institution or through Bruker was also a concern: wherever the same type of equipment was used, an effort was made to standardize the acquisition parameters. In certain cases, however, the experience gained through the initial analysis of a tarocchi deck proved crucial to improve the following campaigns of data collection. For example, only upon close inspection of reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS) data acquired on cards from the Accademia Carrara was the team able to optimize the experimental settings for the subsequent scanning of the Brera deck, which yielded improved results in terms of data resolution and legibility. Multiple instruments using somewhat different parameters were employed for analysis of tarocchi cards at Yale, the Morgan, the Met, and two institutions in Italy, but this did not present a major challenge. Though differences such as spectral and spatial resolution had to be considered, the various types of data collected were sufficiently comparable to allow for identification of the pigment palette on each deck of cards. A separate, forthcoming paper will detail the experimental conditions for the scanning XRF and RIS analysis and describe our efforts to correlate results obtained on different instruments.

During this second phase of the study, scientists from the Art Institute of Chicago were also engaged in the project to conduct in-depth binding-media analysis for the Italian cards using pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS), matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI), and MS-based proteomics. In February 2023, the Morgan and Yale also sent samples to the Art Institute of Chicago for analysis of binding media and green and red glazes applied to the cards.

Data sharing and dissemination

The participation of colleagues at multiple institutions led to a massive amount of data to record, interpret, and share. At the onset of data acquisition, it became clear that the information needed some manner of organization and a method for easy dissemination. The Yale team set up and provided access to a Microsoft Teams site dedicated to the project. A set of channels was created to upload images, files, data, and PDFs of reference articles and books. Monthly Zoom meetings, which were sometimes recorded, were held to discuss the status of data collection, updates on interesting observations, and next steps. The updates could be verbal or via PowerPoint presentation. The updates were non-hierarchical; whoever had something to discuss or a question to ask was on an equal footing with anyone else in the group. Some of the questions that were raised included the amount of barium in the azurite in different decks, the continuing mystery of a few compounds that defy Raman identification, and the composition of glue used to make the pasteboard. The barium question became the focus of technical presentations by one team member that required a deep dive into the azurite data and further investigation into the nature of azurite in medieval manuscripts. Consideration of possible candidates for unidentified pigments has led to an extensive literature search into historic pigment recipes, but a clear answer remains elusive. The composition of the glue raised issues of how to analytically differentiate between the coating or sizing on paper and the glue between the sheets of paper. It became clear throughout the project that the specificity of the inquiry into the materiality of the cards created broader questions about the boundaries of technical analysis and equipment.

Smaller meetings were sometimes held virtually to discuss specific results or to coordinate visits and collaborative analysis. For instance, a sub-team composed of CCR and Art Institute of Chicago scientists held separate meetings to discuss a plan for Py-GC/MS, MALDI, and/or MS-based proteomics investigations on samples removed from the Accademia Carrara cards based on the outcomes of preliminary FTIR analysis. The monthly meetings also provided a general opportunity to stay connected with each other and always ended with an agreed-upon date for the next meeting. Attendance at the meeting was at each group member’s discretion and availability, but they were always well-attended and informative. Zoom and Teams platforms were selected due to the ability of all team members to access them easily.

The accumulation of data from the analysis of the decks made clear that a platform to present the project to the public would focus the research. The idea for an online study day, based on the preliminary results, was proposed and endorsed in late 2021. Feeling that a six-month lead time would allow for the interpretation of the analytical data and creation of presentations, a final date of 21 June 2022 was established. The Tarocchi Virtual Study Day was hosted online by the Thaw Conservation Center (TCC) at the Morgan. The concept of the study day was built around participation by all group members—curators, conservators, and conservation scientists. Invited speakers included curators from the Accademia Carrara and the Pinacoteca di Brera, a specialist in historical playing cards, and an expert in organic pigments. Since the research project was independent of an institutional exhibition calendar or publication, some means of dissemination would be useful to summarize our results, evaluate our assumptions, and develop plans for additional research. Presenting results to the public would also be an opportunity for feedback from a wider audience. In addition, the study day would also provide a tangible result of the time and effort put into the study for Team Tarocchi team members to show their respective institutions.

The virtual study day was conceived as a hybrid of a virtual conference and an in-person study day. It was advertised on several conservation, curatorial, and medieval studies sites and listservs. A dedicated Morgan email account was created to manage requests and inquiries. A study packet with background information on the project and the decks, and bios of the speakers, was sent via email to all registered participants a few days before the study day. The composition of the talks broke down principally into curatorial, conservation, and conservation science groups. The project members believe the virtual study day was a success. It provided an opportunity to invite additional experts with diverse backgrounds, whose comments gave Team Tarocchi new insights, and encouraged interaction between presenters and attendees, as evidenced by the number of thoughtful questions asked following the presentations. The presentations were recorded, edited, and uploaded to the TCC webpage on the Morgan’s website.19 Financial support for the editing of the videos and honorariums for the two unaffiliated specialists was provided by Timothy Young via the Cary Playing Card Collection at Yale. Young’s curatorial and financial support of the project has been central to the success of the project.

Team Tarocchi grew organically from the initial conversation between conservators to the larger multi-institutional, multinational group of engaged team members. Everyone balanced their work responsibilities with this project. Some of the funding sources have been referenced throughout this essay, but it is important to emphasize the funding that continues to make the project viable. Scientific analysis of the Morgan cards carried out at the Met was made possible by NICS; support for NICS is provided by grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Sloan Foundation. Work on tarocchi decks belonging to the Accademia Carrara and the Pinacoteca di Brera was made possible through funding from the CCR “La Venaria Reale.” The costs of shipping the Morgan cards to Yale and the video editing and honorariums of the study day were provided by the Cary Playing Card Collection Fund at Yale. The Morgan Library & Museum provided the institutional infrastructure to host the study day and maintain the talks online on the museum’s website. Every institution contributed in-kind costs that are essential to any research initiative. These costs range from registrar staff time to online and IT support for software and meeting platforms.

Summary of results

While data collected from this technical study will be presented and discussed more thoroughly in a series of upcoming publications along with the associated instrumental parameters, this section provides an overview of the most significant analytical results obtained to date on the Visconti-Sforza decks, with a greater focus on the cards held in United States collections. The goal is to briefly illustrate how the concerted deployment of multiple analytical techniques by individuals working cooperatively at different institutions has allowed us to better understand and compare the materials and construction methods used to prepare the tarocchi decks being studied.

The results discussed here focus on the supports, or composition of the pasteboard, the image layers including underdrawings and use of metal leaf, and the color palette used on the various decks. These three areas address some of the initial questions relating to similarities and differences between decks and what those may mean for attribution and dating of the decks. While the cards from different decks may initially look similar, analysis reveals small but significant differences including the type of metal leaf employed, the use of lapis lazuli or smalt and the layering of blue pigments, and the complexity of the colors used for different decks.

Supports

The decks in the Yale and Morgan collections were made on pasteboards. These were produced by layering and gluing together four or five sheets of laid paper, with a larger sheet of laid paper wrapped around the front. The back of Yale cards is left bare, while the back of Morgan/Carrera cards is painted with sappanwood (Fig. 5). Pasteboard glues are derived from cattle for the Yale deck, and from mixtures of cattle and sheep and/or goat for the Morgan deck.20 Laid and chain lines are visible in both decks. Six similar watermarks, one complete and five partial, were detected on the back of multiple Yale cards. These closely match watermarks found in documents preserved in several Northern Italian repositories within a 250-mile radius of Milan and are dated between 1437 and 1442; none were found on Morgan cards (Fig. 6).

Image layers

Using a combination of XRF, Raman, and imaging techniques, we can see that the image composition appears to have been planned through sequential steps, i.e., a loose sketch drafted with a lead-containing material, such as lead point; carbon-based or iron gall ink underdrawings visible under the bole or through the thin paint layers, serving to refine the initial sketch; and a general outline of the main compositional elements incised in the paper substrate prior to the application of bole. By forgoing the application of a layer of gesso and making the choice to render the preparatory drawings and scratch figure outlines directly in the paper, the artist combined portions of Cennini’s recommendations on illuminating21 and panel painting.22 The artist appears to have followed to the letter Cennini’s instructions in a chapter describing how the contours of figures positioned on gilt backgrounds and the figures’ clothes should be scored in the support using a needle.23 More elaborate decorative incisions and tooling are added after the metal leaf is applied. In some cases, such as in the Morgan The Last Judgment, compositional changes are detected (Fig. 7). For example, the iron map shows that the incised lines outlining the original position of the trumpet held by the angel on the left is lower than in the final version.

After the underdrawing was complete, a red bole layer was painted onto the surface of the cards to adhere the metal leaf to the pasteboard support, imparting to it a warm tone. In both the Yale and Morgan decks, scanning XRF revealed that the bole is composed of an iron-rich clay, mixed with or applied over gypsum. Differing amounts of vermilion, which is present in relatively high quantities in Yale cards, may help yield a different tone to the metal leaf.

Losses, such as those on the Morgan Love, reveal the presence of an ink underdrawing and show that the bole was not applied overall, but rather painted up to and over the perimeters of the figures (Fig. 8).

The gold and silver elemental distribution maps obtained using scanning XRF spectroscopy (Fig. 9) show numerous, often wide areas of overlap of the gold leaf on the Yale court and trump cards suggesting the use of a greater number of smaller pieces of metal leaf or that a greater number of tears and creases occurred during application. By contrast, the Morgan figure cards use larger, often full sheets of oro di metà—produced by hammering gold and silver together into a single leaf—laid across the surface in a neat uniform manner, without any creases or breaks, indicating that the thicker oro di metà was easier to handle than the thinner gold leaf. Comparison of corresponding gold and silver maps for certain Morgan cards allows for the identification of areas where only silver leaf has been used to provide decorative highlights (e.g., the clothing of the figure of God in The Last Judgment and the tunic of the King of Coins as shown in Fig. 9). Tarnishing of the silver over time has imparted a darker tone to the leaf, which is especially evident within the edges of certain cards (Fig. 10).

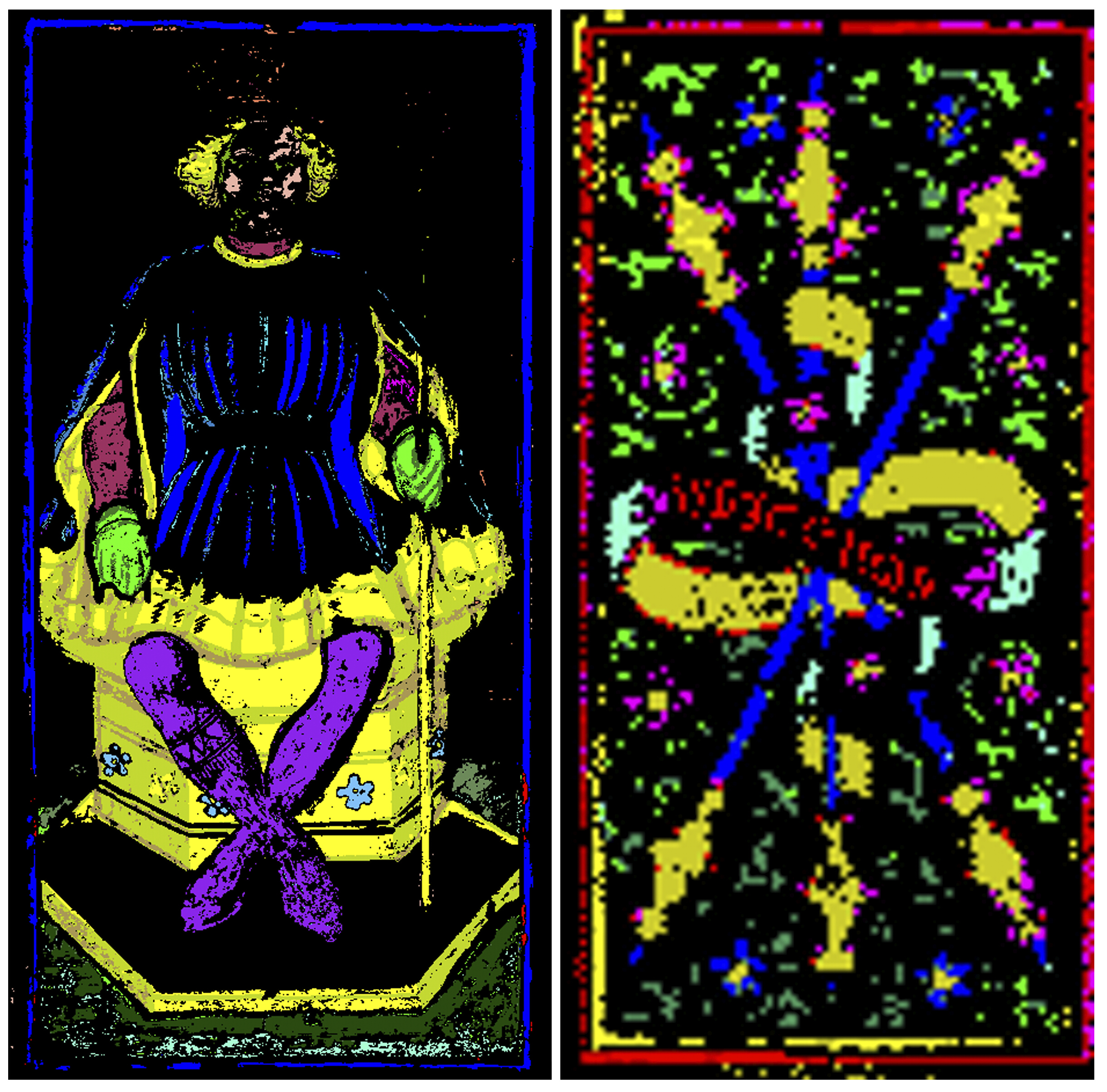

Metal leaf was also used quite differently in the pip cards of the decks that were examined. The backgrounds of the number cards are made with silver leaf for Yale and Brera cards and with lead white for the Morgan/Carrara deck. In both cases, gold leaf was used to create details of the four different suits (Figs. 1, 11). Fig. 11 shows a comparison of the Ace of Coins pip cards from each of the three tarocchi decks. This illustrates how the materials used in the decoration vary, in addition to the patterns of the cards being related but slightly different. The Brera and Yale cards (top and bottom rows) have silver leaf covering the recto, while the Carrara card (middle row) has a lead-rich background, painted with lead white. Like the court and trump cards from the Yale deck, the bole contains an iron earth pigment and vermilion, while the Brera card has only an iron-containing bole under the silver. The maps show that copper-based pigments were only employed on the border of the Brera card, while they were utilized in the decorative designs on the other two pip cards.

Tooling is used extensively in both court and trump cards to animate the large areas of burnished gold and silver leaf: backgrounds are decorated with round or oval punch marks, as well as freehand incised lines (Fig. 12).

Color palette

A critical goal of the project was to identify the pigments and colorants used to create the tarocchi. This was accomplished using a combination of XRF, Raman, SERS, and RIS (Fig. 13). The Morgan deck displays a more complex color palette compared to the Yale deck. Red, blue, and green glazes were applied to both decks as a finishing touch over tooling and punchwork. Organic colorants such as kermes, sappanwood, and folium have been identified in the Morgan deck by SERS, while the Yale deck includes fewer shades, which will also be analyzed in samples that have already been obtained as part of the ongoing study. The blues on Yale cards are azurite and a mixture or layering of lapis lazuli and azurite. Careful analysis using optical and Raman microscopy revealed that in some cases a thin layer of lapis lazuli was laid over a thicker underlying layer of azurite, possibly to conserve the more expensive pigment while retaining the lapis lazuli color. Likewise, in addition to azurite and lapis lazuli, the Morgan deck liberally uses smalt as a blue pigment, either as an underlayer for azurite or in combination with the other inorganic blue colors, but there appears to be little or no indigo and smalt used in the Yale deck. This absence of smalt carries over into the composition of the green pigments. In the Yale deck, green paints include an unidentified copper-based pigment and a mixture of copper-based green with lead tin yellow type I, while many greens in the Morgan deck include complex mixtures of malachite and lead tin yellow type I with azurite, lapis lazuli, and smalt. Lead tin yellow type I is the main yellow employed in both decks, although the Morgan cards contain a second type of yellow-orange pigment based on yellow ocher. Browns in the Yale deck feature iron gall ink24 and a still unidentified brown colorant, while the Morgan deck also displays mixtures of lead tin yellow, vermilion, and carbon black. White and black tones include lead white and a carbon-based black for both decks, with the addition of indigo for the Morgan deck.

The color palette is generally consistent with pigments used at the time in both panel and manuscript painting. Iron gall ink has been frequently identified in underdrawings and the use of inorganic pigments such as azurite, lapis lazuli, vermilion, lead white, copper-based greens (such as malachite and verdigris or copper resinate), and lead tin yellow type I has been commonly reported. Additionally, copper-based glazes mixed with lead tin yellow to create a grass green appear to have been common in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Northern Italian painting.25 Previous studies of organic purple colorants in manuscripts have identified folium in several fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Italian manuscripts.26 The identification of three distinct organic colorants—sappanwood, kermes, and folium—is indeed exciting. However, it is worth noting that the challenges associated with positively confirming these identifications stem from the lack of sufficient or comprehensive published data available for comparison with our results.27 Nevertheless, organic red or pink colorants used in the form of lake pigments or glazes have been frequently described in panel and manuscript painting.

Though binding media analysis is currently ongoing, results to date suggest the use of a whole egg binder for paint areas and a diterpenoid resin for glazes. These are traditional binders that do not readily give a clue about the type of artist who made the cards. Gum arabic, glair (egg white), and parchment size are traditionally cited as the binders preferred by illuminators, while egg yolk and whole egg are usually associated with panel painting. The thin paint layers of manuscript illuminations have made the identification of binders in the past challenging; however, recent case studies28 are uncovering binders with lipidic components more frequently, suggesting the use of egg yolk or whole egg.

Retouching and overpainting are observed on several cards from the Yale and Morgan decks. One of the most significant alterations to the Morgan/Carrara tarocchi deck is the addition of six cards—three held at the Morgan and three at the Accademia Carrara—that are thought to have been created to replace cards that had been damaged, lost, or destroyed. Technical analysis and current scholarship suggest that, while containing different materials, including mosaic gold, a synthetic pigment made of tin (IV) sulfide, such replacement cards might be contemporary to the rest of the deck.

Data acquired from the technical analysis of tarocchi decks held at the Accademia Carrara and the Pinacoteca di Brera are currently undergoing careful examination and interpretation. Carrara cards appear to be mostly consistent with the rest of the deck held at the Morgan, while Brera cards are more similar to Yale cards based on several observed features. Noticeably, one card in the Carrara deck, the Three of Staves, displays unusual materials and techniques, likely pointing to a different hand and time of production.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Team Tarocchi continues to meet via monthly Zoom meetings. Analysis of data is currently ongoing, and updates on any new information and results are the focus of the meetings. The study day was intended as a vehicle to focus and present research results, though it was not meant to preclude additional research or publications. In fact, the data from the cards in Italian collections was in an incipient stage of acquisition at the time of the study day, with much still to be discovered and processed. Publications and presentations are actively encouraged in the group. There are currently several publications in progress by various members either as individuals or in small groups. The project provides the base from which individual members can determine how to publish results relevant to their area of study in the manner that best suits their professional career and on their own timeline. The success of the project to date can be attributed to the shared enthusiasm of the members to fill the knowledge gap on the technical production of Italian tarocchi decks, the consistent organization of meetings, and the openness of the group to ideas and suggestions. The project benefits from institutional support, available funding, remarkably interesting subject matter, and a general bonhomie among teammates.

The project is also not tied to a specific time-based publication or exhibition, which has both positive and negative effects. The positive is that any questions raised can continue to be answered within the group setting and within a time frame that works for interested team members. The downside is that without externally imposed deadlines, day-to-day job requirements may preclude quick resolution to additional questions. One way this has been addressed is through project participants engaging in presentations at a number of conferences. The tarocchi project has provided an opportunity for the personal and professional interests of the conservators and conservation scientists involved to align with priorities and interests at their respective institutions. This project also benefits from an ineffable, and thus not necessarily easily reproducible, set of circumstances—a genuine sense of friendship and kinship among the group members, an abiding sense of wonder and inquiry about the creation of the cards, and a willingness to work cooperatively for an extended period of time.

While the narrative of the tarocchi card project holds valuable lessons for colleagues in the cultural heritage field involved in or contemplating collaborative projects, the extent of its applicability to other institutions necessarily hinges on specific circumstances. Our team operated successfully on a non-hierarchical structure, and the noncompetitive and supportive working approach that we enjoy developed naturally. Our experience underscores the significance of allocating time for collaborators to engage with the objects under study and with one another. It emphasizes the need for well-functioning channels of regular communication for data sharing and interpretation of results, as well as a clearly articulated plan for disseminating the study’s findings.

Acknowledgments

A collaborative project of this scope would not be possible without the generous contributions of many individuals. The authors would like to thank all the members of Team Tarocchi for their expertise, enthusiasm, and collegiality: Anikó Bezur and Marcie Wiggins (Yale IPCH), Lydia Aikenhead, Elena Basso, and Silvia A. Centeno (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), John K. Delaney (National Gallery of Art), Roxanne Radpour (University of Delaware), and Clara Granzotto (The Art Institute of Chicago). We also express our sincere appreciation to the following individuals for their support of the project: Timothy Young (Curator, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Yale Center for British Art, Yale University, formerly Curator, Modern Books & Manuscripts and Cary Collection of Playing Cards, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University), Roger S. Wieck (Melvin R. Seiden Curator and Department Head of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, The Morgan Library & Museum), Colin B. Bailey (Director, The Morgan Library & Museum), Maria Cristina Rodeschini (former director, Accademia Carrara), Paolo Plebani (curator, Accademia Carrara), James Bradburne (Director, Pinacoteca di Brera), Letizia Lodi (Curator, Italian Ministry of Culture, Head of Collections, and Director of the Cabinet of Drawings and Prints, Pinacoteca di Brera), Andrea Carini (Chief Conservator and Coordinator of Conservation Laboratory, Pinacoteca di Brera), Marcello Valenti (Technical Assistant, Pinacoteca di Brera), and Marco Leona (David H. Koch Scientist in Charge, The Metropolitan Museum of Art). We also thank Michele Gironda, Alessandro Tocchio, and their team from Bruker Nano Analytics, as well as Matthew Bloomfield and his colleagues at Renishaw Inc., for the loan of instrumentation and technical assistance. We offer our thanks to Irma Passeri (Yale University Art Gallery) for her contributions to the initial stages of the project and Daniel Kirby (Dan Kirby Analytical Service) who carried out peptide mass fingerprinting analysis of glue samples obtained from the card supports. We extend our sincere appreciation to Lindsey Tyne (Conservation Librarian, Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department, New York University Libraries) for reading an early draft of the paper and for offering constructive suggestions for improvement. We also wish to thank the peer reviewers and editors at Materia for their constructive recommendations that helped us improve the paper.

Author Bios

Francisco H. Trujillo, Drue Heinz Book Conservator, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, NY, USA

Federica Pozzi, Director of Scientific Laboratories, Centro per la Conservazione ed il Restauro dei Beni Culturali “La Venaria Reale,” Venaria Reale (Turin), Italy

Marie-France Lemay, Head of Paper and Photograph Conservation, Yale University Library, New Haven, CT, USA

Richard R. Hark*, Conservation Scientist, Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage, Yale University, West Haven, CT, USA

*Corresponding author

Bibliography

Aceto, Maurizio, et al. “On the Identification of Folium and Orchil on Illuminated Manuscripts.” Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 171 (2017): 461–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2016.08.046.

Bandera Bistoletti, Sandrina. Visconti Tarots of the Brera Gallery. Milan: Martello Libreria, 1991.

⸻, and Pinacoteca di Brera. I tarocchi: Il caso e la fortuna: Bonifacio Bembo e la cultura cortese tardogotica. Milan: Electa, 1999.

⸻, Tanzi Marco, and Pinacoteca di Brera. Quelle carte de triumphi che se fanno a Cremona: I tarocchi dei Bembo: Dal cuore del Ducato di Milano alle corti della valle del Po. Milan: Skira, 2013.

Bonifacio Bembo, “Visconti-Sforza Tarot Cards”, Milan, Italy, ca.1450-1480. Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.630.1-35. Purchased by J.Pierpont Morgan, 1911. 173 x 87 mm. Link to record: https://www.themorgan.org/collection/tarot-cards.

Briquet, Charles-Moïse. Les filigranes: Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600 avec 39 figures dans le texte et 16,112 fac-similés de filigranes. Leipzig: K.W. Hiersemann, 1907.

Cennini, Cennino, and Lara Broecke. Cennino Cennini’s Il Libro Dell’arte: A New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription. London: Archetype, 2015.

Delmoro, “Entre Filippo Maria Visconti et Francesco Sforza: Trois célèbres tarots ducaux,” in Tarots enluminés, 74–75.

Depaulis, Thierry, André Santini, and Musée français de la carte à jouer. Tarots enluminés : Chefs-d’œuvre de la Renaissance italienne. Paris, Issy-les-Moulineaux: LienArt and Musée français de la carte à jouer, 2021.

Depaulis, Thierry. “Imprimait-on des cartes à jouer à Ferrare en 1436?” Playing-Card Journal 40, no. 4 (2012): 252–56.

⸻. “L’apparition de la xylographie et l’arrivée des cartes à jouer en Europe.” Nouvelles de l’Estampe 185, no. 6 (2002–3): 7–19.

⸻, and Bibliothèque nationale de France. Tarot, jeu et magie. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, 1984.

⸻, and Stuart R Kaplan. Cary-Yale Visconti Tarocchi Deck. Stamford, CT: U.S. Games Systems, 1984.

Dummett, Michael. The Visconti-Sforza Tarot Cards. New York: George Braziller, 1986.

Husband, Timothy P. The World in Play: Luxury Cards, 1430–1540. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Kaplan Stuart R. The Encyclopedia of Tarot. New York: U.S. Game Systems, 1978.

Kühn, Hermann. “Lead-Tin Yellow.” In Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics. Volume 2, edited by Ashok Roy, 83–112. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1993.

⸻. “Verdigris and Copper Resinate.” In Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics. Volume 2, edited by Ashok Roy, 131–158. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1993.

Liu, Yun, Tom Fearn, and Matija Strlič. “Photodegradation of Iron Gall Ink Affected by Oxygen, Humidity and Visible Radiation.” Dyes and Pigments 198 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2021.109947.

MacLennan, Douglas, Laura Llewellyn, John K. Delaney, Kathryn

A. Dooley, Catherine Schmidt Patterson, Yvonne Szafran, and

Karen Trentelman. “Visualizing and Measuring Gold Leaf in

Fourteenth- and Fifteenth-Century Italian Gold Ground

Paintings Using Scanning Macro X-Ray Fluorescence

Spectroscopy: A New Tool for Advancing Art Historical

Research.” Heritage Science 7 (2019).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0271-0.

Melo, Maria João, et al. “Iron‑Gall Inks: A Review of Their Degradation Mechanisms and Conservation Treatments.” Heritage Science 10, no. 145 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00779-2

Moakley, Gertrude. The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family: An Iconographic and Historical Study. New York: New York Public Library, 1966.

Olsen, Christina. "Carte da trionfi: The Development of Tarot in Fifteenth-Century Italy." PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1994.

Panayotova, Stella. The Art & Science of Illuminated Manuscripts: A Handbook. London: Brepols, 2020.

Piccard, Gerhard, and Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart. Wasserzeichen Fabeltieren: Greif, Drache, Einhorn. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1980.

Pozzi, Federica, and Elena Basso. “The Network Initiative for Conservation Science (NICS): A Model of Collaboration and Resource Sharing Among Neighbor Museums,” Heritage Science 9 (2021): 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00559-4.

Richter, Ernst-Ludwig, and Heide Härlin. “The ‘Stuttgarter Kartenspiel’: Scientific Examination of the Pigments and Paint Layers of Medieval Playing Cards.” Studies in Conservation 21, no. 1 (1976): 18–24.

Turner, Nancy K. “Surface Effect and Substance: Precious Metals in Illuminated Manuscripts.” In Illuminating Metalwork: Metal, Object, and Image in Medieval Manuscripts, edited by Joseph Salvatore Ackley and Shannon L. Wearing, 51–110. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110637526-002.

Notes

-

Tarocchi cards were originally referred to as carte da trionfi, possibly a reference to Petrarch’s poem I Trionfi dating from the mid-fourteenth century. Thierry Depaulis, introduction to Tarots enluminés: Chefs-d’oeuvre de la Renaissance italienne, ed. Thierry Depaulis (Paris, Issy-les-Moulineaux: Musée Français de la Carte à Jouer and LienArt, 2021), 19–20. See also Gertrud Moakley, The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family: An Iconographic and Historical Study (New York: New York Public Library, 1966). ↩︎

-

Depaulis, introduction to Tarots enluminés, 14. ↩︎

-

Depaulis, 18. ↩︎

-

Unlike chess, where skill and strategy were necessary, dice and certain card games were seen as sinful because they involved chance or gambling. Interestingly, card playing was forbidden in Milan in 1420 during Filippo Maria Visconti’s reign and again by Francesco Sforza during the first year of his reign in 1450. See Christina Olsen, From Low to High: The Emergence of Tarot, in “Carte da trionfi: The Development of Tarot in Fifteenth-Century Italy” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1994), 80–136. ↩︎

-

Each suit has ten number, or pip, cards and four court cards, King, Queen, Knight, and Page (sometimes referred to as Knave or Valet). ↩︎

-

Unlike the Morgan and Brera decks, which feature the traditional arrangement and number of court, trump, and pip cards, the Yale deck includes atypical female Knight and female Page cards for each suit, as well as three theological virtues, Faith, Hope, and Charity. These additional cards bring the hypothetical total number of cards for the Yale deck to eighty-nine. ↩︎

-

Bembo, Bonifacio, [Visconti di Modrone Tarocchi], [Italy]: [publisher not identified], [1445?]. Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, ITA109. 189 x 90 mm. Link to record: https://hdl.handle.net/10079/bibid/15349690; link to images: https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2002878. ↩︎

-

Thierry Depaulis and Stuart R. Kaplan, Cary-Yale Visconti Tarocchi Deck (Stamford, CT: U.S. Games Systems, 1984), 16. ↩︎

-

Roberta Delmoro, “Entre Filippo Maria Visconti et Francesco Sforza: Trois célèbres tarots ducaux,” in Tarots enluminés, 74–75. ↩︎

-

Their approximate dimensions (height x width) are as follows: Yale, 189 x 90 mm; Brera, 178 x 89 mm; Morgan, 173 x 87 mm. ↩︎

-

The Met Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, January 20–April 17, 2016. ↩︎

-

The results of only a very small number of technical studies of playing cards have been published in the last several decades. To our knowledge, the technical analysis of the gilded and hand-painted “Stuttgart Playing Cards” (ca. 1430, Germany) housed at the Landesmuseum Württemberg in Stuttgart is probably the most in-depth technical study published to date. See Ernst-Ludwig Richter and Heide Härlin, “The ‘Stuttgarter Kartenspiel’: Scientific Examination of the Pigments and Paint Layers of Medieval Playing Cards,” in Studies in Conservation 21, no. 1 (February 1976): 18–24. Results from more modest technical analysis performed on cards from three other decks have also been published. For the “Chariot” tarot card attributed to the “Maître du Chariot d’Issy” (1441–1444, Lombardy) and acquired by the Musée Français de la Carte à Jouer in 1992, see Depaulis, Tarots enluminés, 80. For the “Charles VI Tarot” (1475–1500, Northern Italy) held at the Bibliotèque Nationale de France, see Thierry Depaulis, Tarot, jeu et magie (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, 1984), 40–41. For the “The Cloisters Playing Cards” (1475–1480, Netherlands), part of the Cloisters Collection, see Timothy P. Husband, The World in Play: Luxury Cards, 1430–1540 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015), 82. ↩︎

-

In a guidebook that accompanies a facsimile edition of Yale’s Visconti di Modrone deck, Thierry Depaulis refers to Stuart R. Kaplan’s Encyclopedia of Tarot (vols. 1 and 2), which “reproduces or mentions thirty decks or sets—all incomplete—representing some 340 cards, stored in museums, public libraries, and private collections.” Depaulis and Kaplan, Cary-Yale Visconti Tarocchi Deck, 16. ↩︎

-

The conference organized by the Fitzwilliam Museum (Cambridge, UK) brought together conservators, conservation scientists, art historians, and manuscript scholars to highlight and showcase interdisciplinary collaborative research and recent advances in the technical analysis of illuminated manuscripts. It accompanied the exhibition Colour: The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts, held at the museum July 2016–January 2017. ↩︎

-

The NICS was relaunched as Scientific Research Partnerships on 29 June 2023. ↩︎

-

Recent examples include the exhibits Tarots enluminés: Chefs-d'oeuvre de la Renaissance italienne at the Musée Français de la Carte à Jouer in Paris and The World in Play: Luxury Cards, 1430–1450 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cloisters in 2016. Examples of websites and forums include the “Tarot History Forum” (https://forum.tarothistory.com) and “The World of Playing Cards” (https://www.wopc.co.uk/italy/visconti). Frank Trujillo and Roger S. Wieck from the Morgan Library & Museum recently hosted a very well-attended, members-only, hour-long live virtual webinar titled “Secrets of Medieval Tarot at the Morgan Library,” organized by Atlas Obscura, that centered on the Visconti-Sforza tarocchi deck. ↩︎

-

Through funding from the Andrew W. Mellon and Sloan Foundations, NICS (now Scientific Research Partnerships) currently supports eleven museums in New York city, including the American Museum of Natural History, Brooklyn Museum, Central Park Conservancy, Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, Frick Collection, Hispanic Museum & Library, MoMA, Morgan Library & Museum, New York Public Library, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and Whitney Museum of American Art. For an overview of NICS collaborations, see Federica Pozzi and Elena Basso, “The Network Initiative for Conservation Science (NICS): A Model of Collaboration and Resource Sharing Among Neighbor Museums,” Heritage Science 9 (2021): 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00559-4. ↩︎

-

The Cary Collection of Playing Cards was developed by Melbert B. Cary Jr, a wealthy importer, in partnership with his wife, Mary Flagler Cary. Together, they collected playing cards until his death in 1941, after which Mrs. Cary continued to add examples from around the world. Following Mrs. Cary’s death in 1967, the collection was presented to Yale, along with funds for its maintenance. For more information about the Cary Collection of Playing Cards, see http://carycards.beinecke.library.yale.edu/CaryEssaysWeb.htm. ↩︎

-

For detailed information about the Tarocchi Virtual Study Day, held on 21 June 2022, see: https://www.themorgan.org/thaw-conservation-center/tarocchi-virtual-study-day. ↩︎

-

Daniel Kirby performed peptide mass fingerprinting, also known as ZooMS, on multiple adhesive samples from Yale and Morgan cards in the summer of 2021 to identify the animal source of the glue. ↩︎

-

“If you want to do illuminations, you need to draw figures, foliate decorations, letters or whatever you want with lead point or a stylus on paper (that is, in books) first. Then you need to reinforce what you have drawn finely with a quill.” Cennino Cennini and Lara Broecke, “[Chapter 171] T100 ‘A short section on illuminating,’ M. CLVII,” in Cennino Cennini’s Il Libro Dell’arte: A New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription (London: Archetype, 2015,) 203. ↩︎

-

“Chapter 122. How, to start with, to draw on panel with charcoal and reinforce with ink,” in Cennini and Broecke, 158. ↩︎

-

“When you have drawn your whole ancona, get a needle attached to a stick and start scratching along the outlines of the figure where they run alongside the grounds which you have to gild, as well as the borders that need to be done on the figures’ clothes and special draperies that are done in cloth of gold.” “Chapter 123. How you should mark the outlines of the figures to be positioned on gold grounds,” in Cennini and Broecke, 159. ↩︎

-

Freshly made iron gall is generally black or blue-black in color. As it ages, the color can shift from black to brown. While the discoloration mechanism is not yet fully understood, it has been suggested that the ink composition and environmental factors such as light, oxygen, and relative humidity might play a role. ↩︎

-

Hermann Kühn, “Verdigris and Copper Resinate,” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Volume 2, ed. Ashok Roy (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1993), 148. ↩︎

-

Although the colorant was identified mostly in decorative filigrees rather than in paintings, the results show that folium was available and used as a colorant in Italy at the time. See Maurizio Aceto et al., “On the Identification of Folium and Orchil on Illuminated Manuscripts,” Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 171 (2017): 461–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2016.08.046. ↩︎

-

Organic colorants are often defined in the literature as “insect-derived” or “plant-derived,” if not just “organic red glaze or lake.” A possible reason for that lies in the fact that analytical techniques currently enabling conclusive identification of these materials, such as SERS or MS, require highly specialized technical skills and are not widely available to museums or research institutions. ↩︎

-

See the case studies in Stella Panayotova, The Art & Science of Illuminated Manuscripts: A Handbook (London: Brepols, 2020). ↩︎