The industrialization of the nineteenth century brought new changes to society with emerging technologies and new ways of living. Women started to fight for their rights and their freedom and for control over the way they dressed. As the Victorian era waned, the modern woman sought new challenges to speak up for herself and to fight for her independence. From this activism the movement known as “dress reform” was born in England, emphasizing ease of wear and comfort in women’s day-to-day dress. Liberty & Co., a London-based British fashion house, became the forerunner of this style, creating non-restrictive, embroidered, and decorated dresses based on designs from antiquity. The Netherlands followed this trend and exported it to their colonialists in Indonesia who followed the European fashion. Very few samples have survived in museum collections; however, as will be seen in this research, there are several preserved in the Kunstmuseum Den Haag fashion and costume collection, particularly a dress (K-98-3000) owned by Anne Beatrix Hoogesteger. The dress, never exhibited since it entered the collection in 1997 and described in the museum database as very damaged, reflects a completely new shape due to the transformation undertaken to accommodate the wearer’s pregnancy in 1908, keeping few of the original 1902–3 design elements. Our research delves into the complexity of its conservation treatment, which aims to restore much of the original design as well as to further understand its materiality. Through scientific analysis, it was discovered that the silk’s poor structural condition was due to the use of a nineteenth-century technology known as sulphur stoving. This contemporary process is poorly documented in modern literature but its identification sheds new light on the potential condition issues of weighted silks.

VI. The Influence of Liberty & Co. in the Dress Reform Movement: The Research and Conservation Treatment of a Rational Dress

- César Rodríguez Salinas

- Madelief Hohé

- Livio Ferrazza

Introduction

Inspired by the characteristic tenets of dress reform, a so-called rational dress in the collection of the Kunstmuseum Den Haag (K-98-3000; Fig. 1) will be the main focus of this article. The dress reflects evidence of being reused, a deliberate choice by the wearer, Anne Beatrix Hoogesteger (1873–1951), against the constant changes in fashion and to accommodate her changing body and the demands of breastfeeding her only child, Anne Marie Christien (1908–1996).1 The maternal reuse is evident through the presence of two dark brown stains on the inside lining near the breasts and alterations that relaxed the waistline (Fig. 1). Described in the database as a possible creation by Liberty & Co., the dress does not have the original label that would have been placed at the waistband. The missing label in combination with the partially missing smock work at the front, the possible alterations at the neckline, and the very shattered silk make the dress an unlikely candidate for exhibition but an interesting piece for further research.

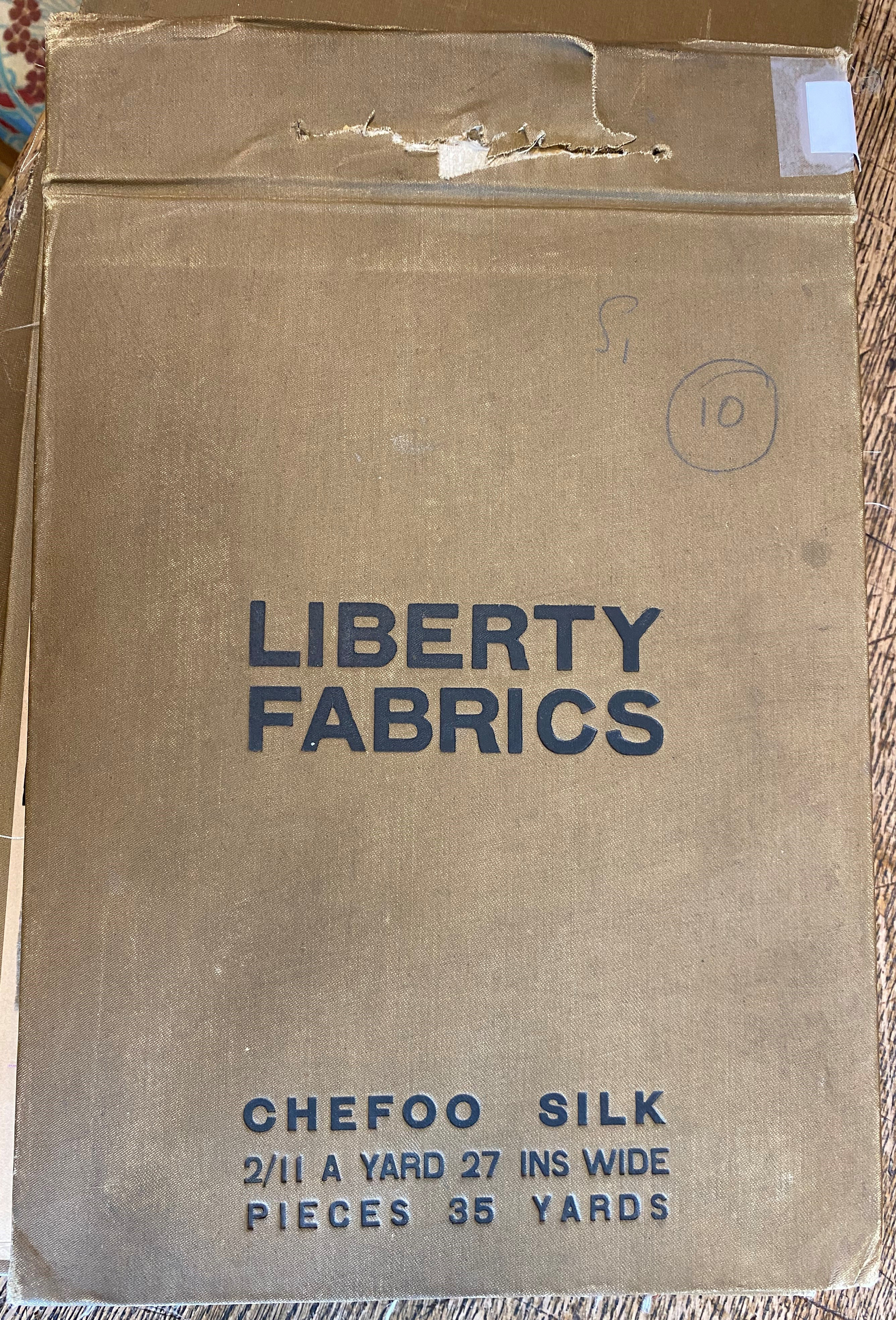

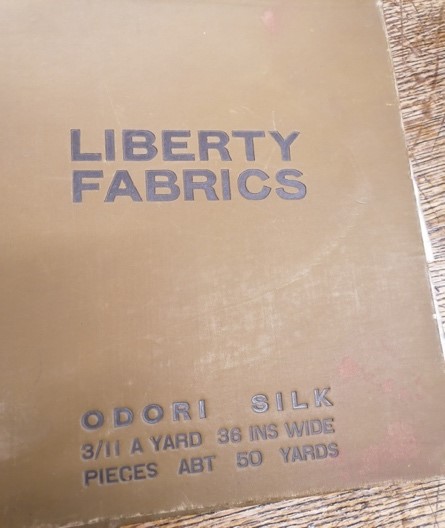

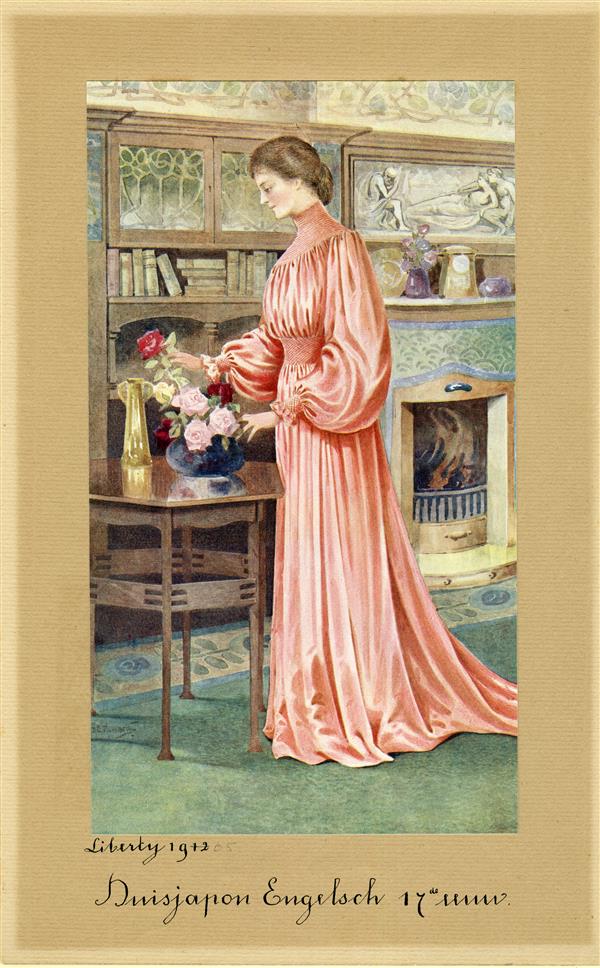

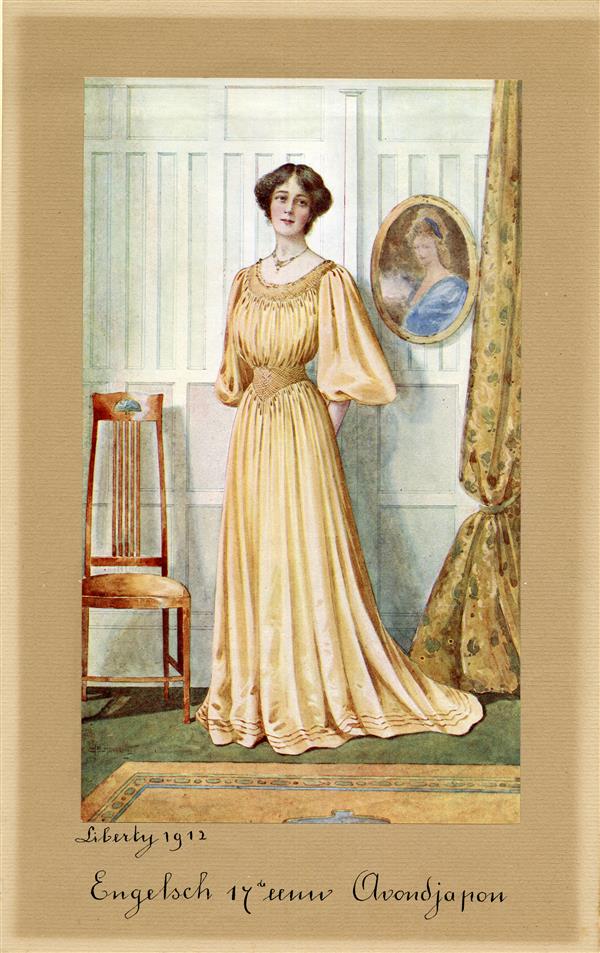

The attribution to Liberty was based on similar dresses in the collections of the Kunstmuseum Den Haag and the Centraal Museum Utrecht, and a comparison to prints of contemporary Liberty dresses showing similarities with this dress.2 Comparisons to similar dresses in the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1995-82-1) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (1986.115.5)3 highlighted similar decorative smock elements and the colorful rust-pink silk. These colored silks became fashionable at the beginning of the nineteenth century, especially in Liberty designs, as confirmed by samples in the Liberty archives showing a wide range of pink silks including silks called Canton, Chefoo, Mitra, and Odori, just to mention a few (see Fig. 2).

Technical and scientific analyses suggest that dress K-98-3000 is more likely a design influenced by Liberty than an original surviving piece made by the firm. Founded in 1875 by Arthur Lasen in London, Liberty exerted enormous influence on women’s wardrobes at the end of the nineteenth century, specifically through luxury products such as cashmere, pongees, and wild silks in a wide range of nuanced colors.4 Lasen saw a new opportunity to create beautiful designs that were inspired by the 1860s artistic dress movement, medieval fashion, and the pre-Raphaelites, creating so-called tea gowns or aesthetic dresses. This new style garnered support from dress reform activists worldwide, making Liberty a source of inspiration to other fashion houses and skillful seamstresses. The presence of the clothing size (46) seen in the interior of K-98-3000 (see Fig. 1), notably absent from the Philadelphia dress, links the dress to the then-emerging practice of prefabricated body linings that were sent by pre-order to local fashion houses, where they were attached to the outer layers of the dresses created there.5 The size numbering in the interior of dresses has also been noted in other pieces from the KMDH collection from the same time period.

Due to the financial success of Liberty designs, the company expanded, opening shops in other countries, including the Netherlands, where textiles and dresses were sold under the Dutch brand Metz & Co.6 This Dutch expansion may have been led by Joseph de Leeuw (1872–1944), who beginning in 1904 showcased Liberty fabrics and dresses for Dutch citizens.7 These luxurious rational dresses were imported directly from Liberty in London to cities such as Amsterdam and the Hague.8 As a result of this rich market, Dutch museums such as the Kunstmuseum Den Haag and the Centraal Museum Utrecht now have some surviving Liberty pieces in their collections as well as pieces influenced by the British fashion house (see Fig. 3). In the Netherlands, there are a few surviving samples of reform dresses that appear to be drawn directly from Liberty creations, as is the case for two blouses stewarded by the Amsterdam Museum (KA 20031, KA 20032)9 and for dress K-98-3000. The following discussion will summarise the study carried out on this dress, in which science, textile conservation, and history help us to understand the influences present at the moment of its creation, its production, and the conservation options for preserving it.

Dress Reform

Dress K-98-3000 encapsulates the fashion trends stemming from various political movements related to women’s dress at the end of the nineteenth century. Despite being dated to the beginning of the twentieth century, the dress studied reflects a particular period of change when many women turned away from the rigid Victorian fashion of corsets in favour of more comfortable pieces. This was especially true for women who needed designs for a life that included working outside the home, sporting, or biking. In the Netherlands, reform dresses were specially worn by modern, independent upper-class women, who wanted to take part in all the activities modern life afforded them, and therefore needed to move freely in their clothing, and had the financial means to acquire such a costly wardrobe. Many of these Dutch Women were part of the Vereniging ter Verbetering van Vrouwenkleding (Association for the Improvement of Women’s Clothing; founded in 1899), which promoted dress reform in the country. However, there were certainly also influences coming from Germany, Belgium, and England; the latter was one of the leading countries at the time, creating on 2 July 1890 at Morley Hall in London the so-called Healthy and Artistic Dress Union (H&ADU), which aimed for women to wear dresses that did not compromise their health and ensured their free movement.10 This new movement was led by the dress reform followers in the 1850s, probably inspired by the Pre-Raphaelites in 1848, who encouraged women to wear less restrictive dresses.11 The H&ADU’s main goal was practicality and comfort, reacting against the Victorian aesthetic that dictated that women wear strict underpinnings such as corsets and crinolines, often leading to damage to their muscles and organs, and reshaping of their ribcages. Dress reform activists then introduced a new style of underwear in lightweight, breathable materials that allowed women to sweat. For that reason, tricot fabrics were made with undyed cotton, ensuring breathability and easy washing. Different stays were also developed without baleen supports to help women transition from rigid corsets to more comfortable creations.12 As a consequence, a new garment was born that had an international impact, traveling from one country to another under the name of “rational dress.”13 The influence of rational dress in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century can be traced through the very similar creations found in museum collections across multiple countries. The rational dress from Palazzo Morando (SN42) in Milan, for example, is made with materials and in a pattern similar to another rational dress from the KMDH collection (K-32-1973; Fig. 4).

Inspired by antiquity, this new form of dress sought to embody the most important aspects of free movement, the absence of pressure over any part of the body, and the prevention of extra weight when the dresses were worn.14 Based on previous experiences, women believed that the use of rigid stays and corsets as well as long, heavy skirts compromised their health, resulting in sickness and changes to the anatomy of the wearer.15 Magazines such as the British Aglaia and French La Mode Bagatelle spread the word, showing the way the new dresses were constructed.16 This new movement lasted at least till the end of the century in England, before handing over the lead to other countries including Germany and Austria, with notable figures such as Maria Van der Velde, Anna Muthesius, and Emilie Flöge and her sisters, co-owners of the salon Schwestern Flöge in Vienna—all of whom promoted a new style of dress that was far from the previous norms.17 In the Netherlands this was followed by the so-called Vereeniging voor Verbetering van Vrouwenkleeding, which espoused the ideas of freedom, health, and functionality for women in society with powerful influences from philosophy, spiritualism, and theosophy.18 Organizations grew out of these collaborations such as the De Wekker (lit. “alarm clock,” with its suggestion of “waking up”) in the Hague, where reform dresses were put on sale.19 The way a person dresses always makes a symbolic statement, and reform dress played an important role in promoting comfort and self-sufficiency as the dress was developed without baleens, with a slightly marked waistline, and with easy closures to help women dress without assistance. The most radical dress reformers did not care about fancy embroidery; they simply wanted to move freely in their clothes without a corset and without a train. New schools were also opened such as the Vakschool voor Verbetering van Vrouwen- en Kinderkleeding (Vocational School for the Improvement of Women’s and Children’s Clothing), where girls received sewing instruction (such as embroidery, cutting, and drawing) in combination with art history lessons.20 Liberty & Co. inspired many of these women through the ways that the firm’s dresses were constructed and by the freedom they offered.21 Maandblad seemed to have been one of the few Dutch magazines that encouraged readers to create reform dresses by including fashion illustrations and drawing patterns. They also published long discussions in which they argued that dress reform was not “fashion” but simply kleding (clothing).22 This social movement influenced the ways that fashion designers created their collections. In France, for instance, Madeleine Vionnet and Jeanne Paquin (with their collections at the beginning of the century) and Paul Poiret (who worked alone before he formed his own fashion house, at the House of Doucet) created dresses that did not need the rigid underpinnings seen years earlier.23 However, those creations did not totally eliminate the constricted silhouette generated by the use of the corset, and they continued to force the wearer to hold an upright position through complex constructions, placing some of the French couturier designs somewhere between beauty and comfort.24 Carin Schnitger, among others, has pointed out the similarities between an evening dress from Paul Poiret made in 1911 and a reform dress from the KMDH collection (K 161-1974) dated 1913, showing an interest in the new dress movement among French fashion designers.25 Liberty, while incredibly influential, was not the only source of inspiration for women in the Netherlands, as evidenced by the apparent interest in other dress reform designers including French designer Jeanne Victorine Margaine-Lacroix26 and Belgian designer Madame de Vroye, whose creations were heavily publicized in the contemporary Dutch press.27

Anne Beatrix Hoogesteger’s dress followed—in Indonesia—the aesthetic elements in Liberty creations in combination with lightweight materials that were meticulously chosen to create a comfortable dress, along with desirable, decorative elements such as lace, popular with reform women.28 Liberty was a source of inspiration rather than an attainable goal as the creations of the British house were made with expensive materials affordable solely by wealthy clientele. A clear example of the cost divide can be found in Liberty silk catalogues distributed to customers, such as one from 1883 where the prices of the silks ranged from 21 shillings to 70 shillings for a seven-yard section. Plain-weave silks similar to dress K-98-3000 were more affordable but still not attainable for every customer.29 The trend of lightweight materials rose following discussions in 1883 at the National Health Exhibition, where the health of individuals and their hygiene were discussed.30 The simplicity in construction and the low-quality materials in dress K-98-3000 followed the ideals of rational dresses, where the focus was not placed on the beauty of the object but on practicality and simplicity.

Influences

The close similarity between dress K-98-3000 and Liberty designs seems to have been made possible by the firm’s publication of Dress and Decoration in 1905, where many women and seamstresses discovered the new fashionable silhouettes and then replicated them.31 Specific illustrations may have been the inspiration for the silhouette of dress K-98-3000 (Fig. 5). Many of Liberty’s creations were decorated with meticulous smock work following the influence of Mother Goose, or The Old Nursery Rhymes by Kate Greenaway (1846–1901) in 1881. This trend peaked in the last years of the nineteenth century, extending to the fashion garments of children that also followed the style of Greenaway. KMDH holds a few of those garments made for children, including a light brown velvet Liberty dress (Fig. 6).

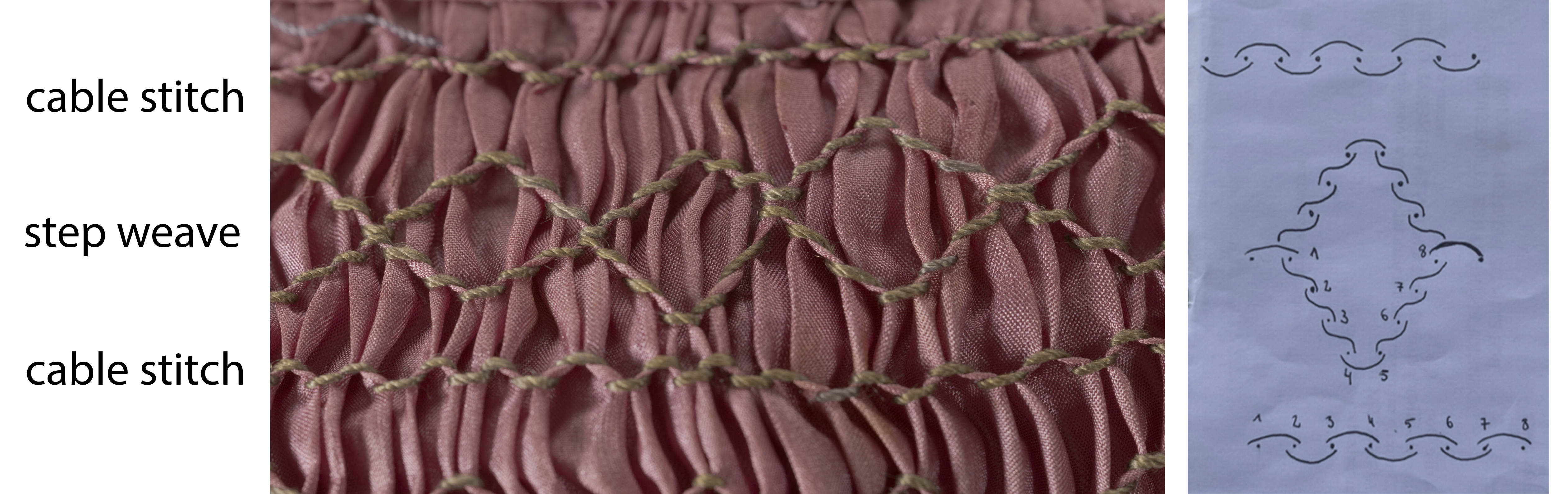

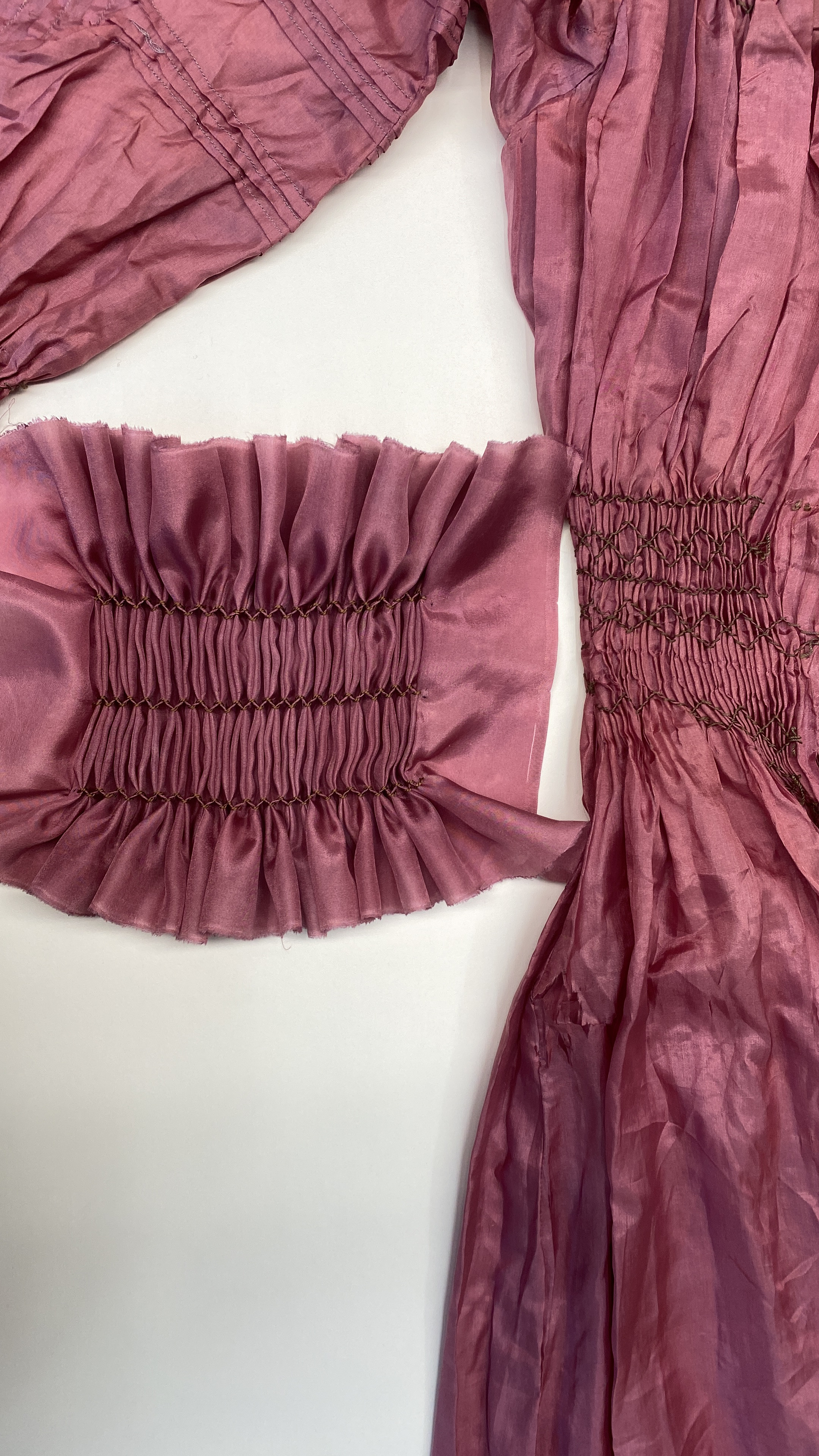

Smock work on dresses gave movement to the sleeves and yoke, and became very fashionable, especially after the 1880s.32 Its use also had a strong social value connected with the history of smock work and its use in the past, but also with the Arts and Crafts Movement, which emerged when industrialization was at its peak.33 However, the study of the smock work present on K-98-3000 did not show characteristics similar to original Liberty dresses, which have complex compositions with double threads and chromatic ombre effects.34 The smock work on the KMDH dress showed a rather simple composition with a single thread made with two types of stitches: the step wave stitch—also known as the zigzag stitch or baby weave—and the cable stitch. Equally, one of the most famous symbols promoted by the British house—identified as an embroidery flower—was also missing, and no other references suggest a link with the British fashion house. This was further confirmed by the absence of visible buttons at the back that always accompanied Liberty creations (see Fig. 7).35

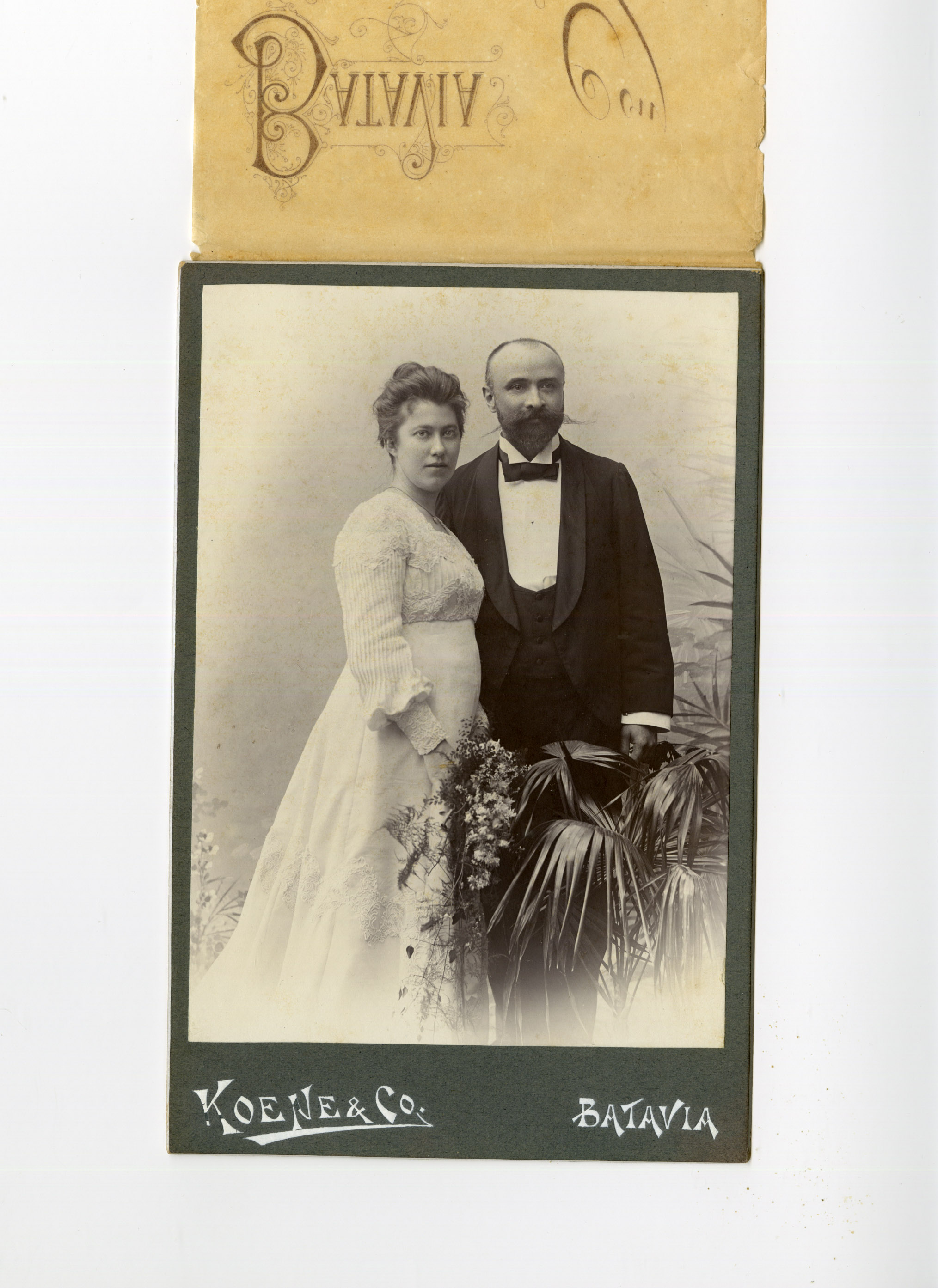

In order to understand the possible origins of the KMDH dress, we first looked at other items from Hoogesteger’s wardrobe, which included local informal house garments, worn by the Dutch in Indonesia as negligee wear at home, based on traditional Indonesian dress such as sarong and kebaja for women and baadje and slaapbroek for men.36 These garments were made following the Western taste for batik fabric, an adoption from Eastern fabrics.37 These garments were informally used by Dutch citizens at home, and could also be worn on their own porch when entertaining visitors; they were not worn outside one’s home, as for those visits a Western-style dress was seen as appropriate for both men and women. By the end of the century, the Dutch communities living in the Dutch colonies imported and exported all manner of textiles to Europe, which were later sold to wealthy women as luxury items (see Fig. 8).38 The diverse wardrobe in the Dutch colonies prioritized comfort and flexibility for a Westerner living in the warm and humid weather. This is the case for a white silk wedding dress from 1903 (K-43-1997) constructed in rational style with a label that can be traced to the fashion house Eug. Roussel. This Indonesia-based dressmaker frequently advertised in a variety of Dutch Indonesian newspapers including De Preanger Bode (9 March 1907) and the Bataviaasch nieuwsblad (3 November 1911), offering tailor-made dresses as well as sewing classes, especially for Western women. The press published information on modern rational dresses along with the latest fashions, including details on Liberty fabrics and dresses. In addition to the wedding dress, there is a cream-colored, wool, reform-style dress (K-44-1997 1-3), a pink cotton dress with a print design (K-45-1997; both ca. 1903), and a brown dress with white lace trim and green silk accents (K-46-1997; ca. 1907), all of them following the characteristic style of the dress reform movement. A close examination of the dresses indicates that they were made following the same tenets of flexibility and comfortability to suit Indonesia’s warm and humid climate, using lightweight materials like that of K-98-3000.

Anne Beatrix Darlang-Hoogesteger

The dress was given to the museum in 1997 by Mrs. B.E.C.T. Bart Bruinink, granddaughter of Anne Beatrix Darlang Hoogesteger (1873–1951). Anne Beatrix Hoogesteger was born in Indonesia (Java) on 25 November 1873 to Dutch parents. Although born in the East, her European roots were an important part of her life and were transmitted by her parents, Marie Marguérite Jeanette Hermine Gortmans and Pieter Hoogesteger. The presence of Dutch families in Indonesia by the end of the nineteenth century was a direct consequence of Dutch colonial activities, especially after the Suez Canal was opened in 1869. This made the route to travel much shorter, and many more Dutch women traveled there, to live with their families or husbands, or to get married. This certainly appeared to be the case for the Hoogesteger family, who journeyed from Rotterdam to Indonesia, where Marie Marguérite gave birth to her children, including Anne in 1873.39 Anne would go on to marry Frederik Filip Franciscus Darlang (1863–1909) on 27 April 1903 in Meester Cornelis (Fig. 9). Some years later, Anne gave birth to her only child, Anne Marie Christien Darlang on 10 December 1908 in Samarang, Indonesia. The family stayed there at least until Frederik’s death in 1909, after which a grieving Anne would return to the Netherlands with their daughter. During their time in Indonesia, the family earned a good reputation and material luxury, enhanced by Frederik’s post with the Dutch Department of Justice.40 Unfortunately, little information is known about Anne following her departure from Indonesia. The museum’s archives offer no further records that expand on Anne’s potential involvement in any of the reform movements that were so popular in the Netherlands at this time in cities such as Amsterdam and the Hague. Her surviving wardrobe offers only a narrow view of her adult life in Indonesia, so any speculation on her childhood or return to Europe is fruitless at best.

Technical and scientific analysis of the dress

Construction and confection

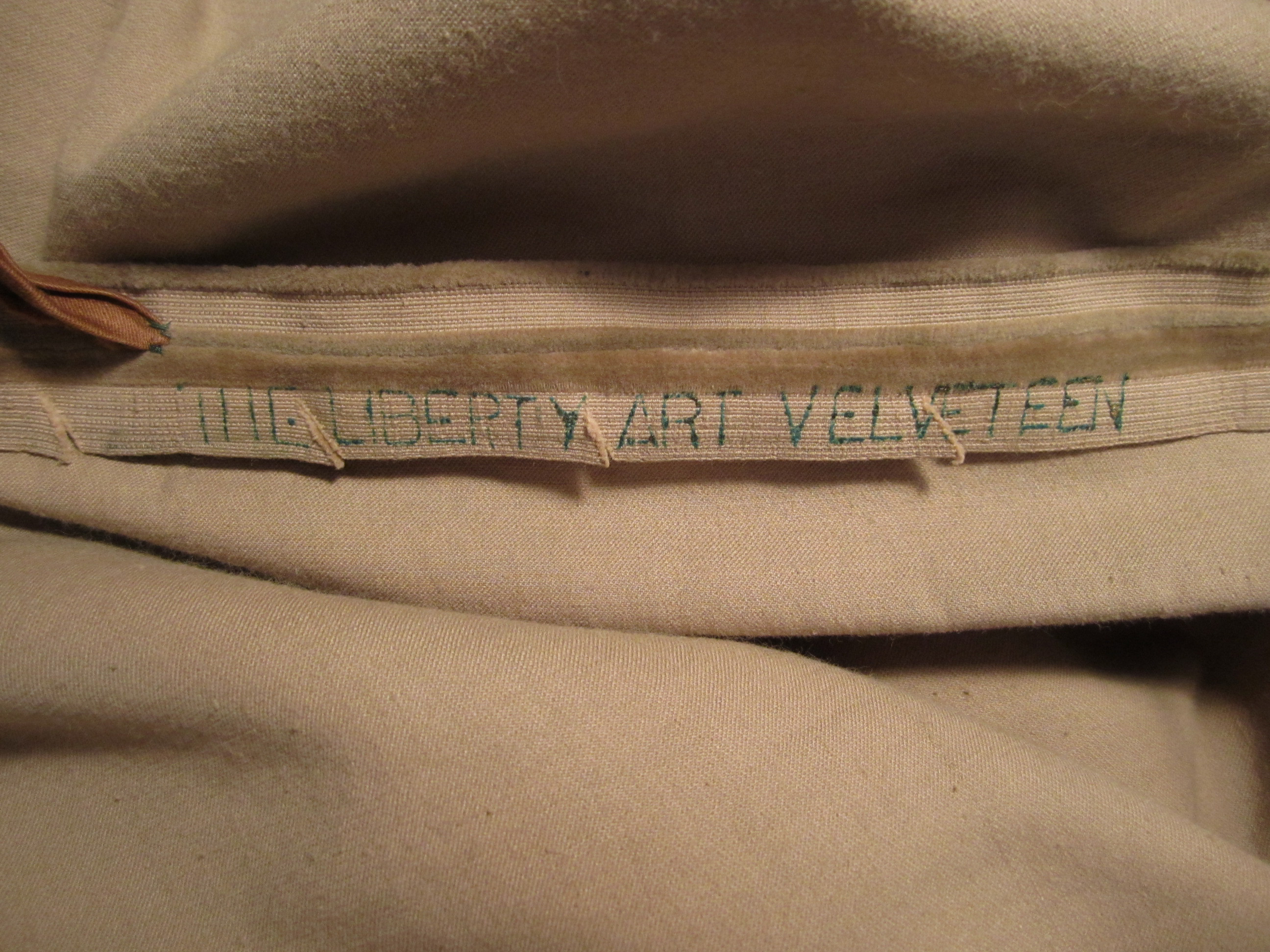

Made with rust-pink silk, the dress (ca. 1902–3) shows a high-necked collar of mechanical tulle reinforced with celluloid stays on the inside. In the back, the dress is closed with metal hooks that fit into the silhouette at the front. Both the front and back below the waistline show a simple, V-shaped smock design that was also used for decorating the long sleeves around the wrist, bust, and rear opening. The inside is lined with a very fine batiste cotton that is fitted at the waist by the addition of darts and sewing-machine seam allowances. Those are particularly visible at the small pleats seen at the sleeves and at the front and back of the skirt at the bottom, leaving the thread as a decorative element over the upper surface with short stitches. The fabric used shows an industrial production by the number of threads and uniformity in thickness achieved in both directions (warp/weft). The construction of the dress indicates that the fabric has been cut in only one direction using the grain for the front and also for the back. Unfortunately, the edges at the interior of the seam allowances represent inferior workmanship as they were not overcast after the fabric was cut to help avoid unravelling and fraying edges. This led to the loss of much of the original selvages, where fashion houses such as Liberty stamped their logo alongside the entire length as their trademark. This loss made it impossible to confirm that the fabric was produced by the British house, as we might have seen in other dresses from the KMDH collection (see Fig. 6).41 The upper part of the dress was finished with a very delicate mechanical tulle that shows beautiful plumet forms surrounded by metal threads. This extra layer was sewn over the smock work with silk used for the construction of the dress, covering some of the original smock areas underneath as seen in Figure 10.

Finally, the decorative elements presented on the dress in the smock areas were made with a single thread in combination with two types of stitches; step wave and cable stitch. Both are worked in a similar manner by passing the needle up through a pleat from right to left and returning the thread in the reverse direction. The difference between the two types of stitch is marked by the position of the thread; one is diagonal (step weave) and the other (cable stitch) is horizontal, as labelled in Figure 11.42

Scientific Analysis

Since the silk was very fragile, it was decided to subject the material to thorough scientific analysis to limit future handling. This step was crucial for us since the dress was labelled for many years as weighted silk and not given the chance to be exhibited as a preventive measure. Its characterization would also help us to conclude more about its production quality since similar dresses from other museum collections labelled Liberty do not show the same level of shattering.

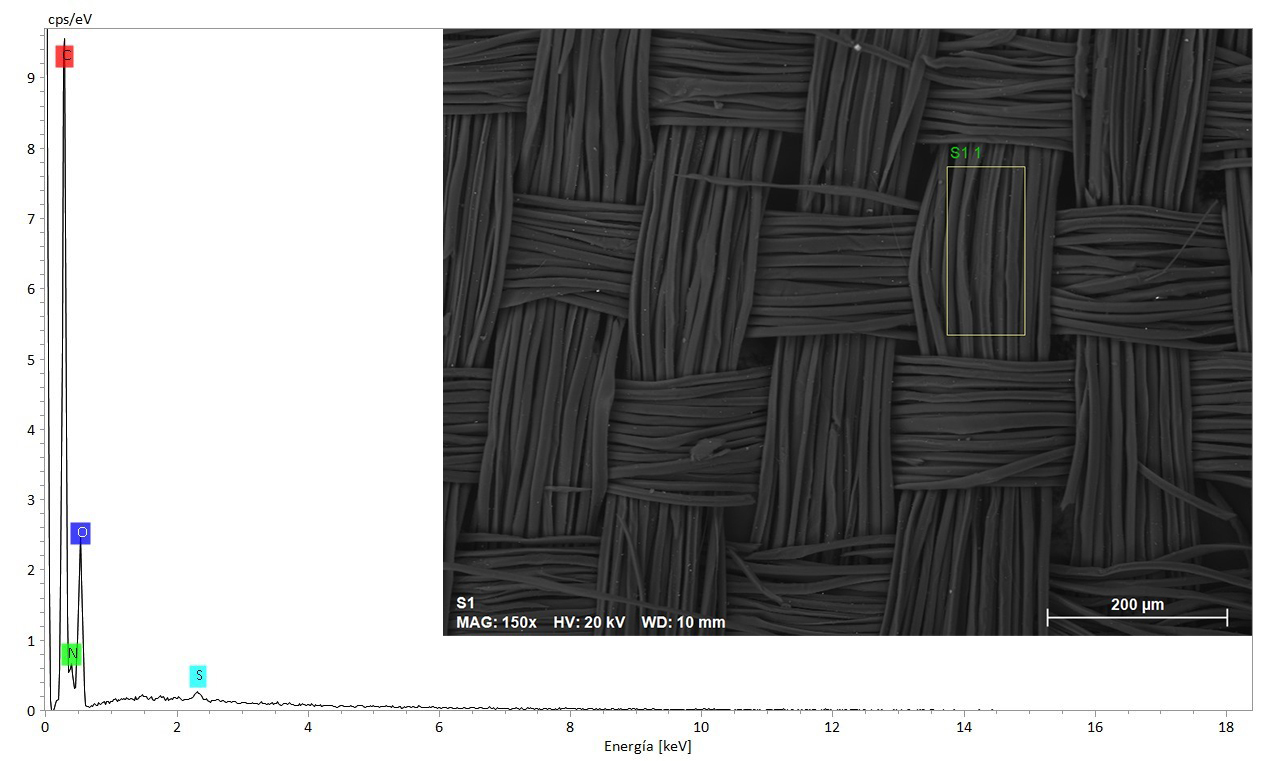

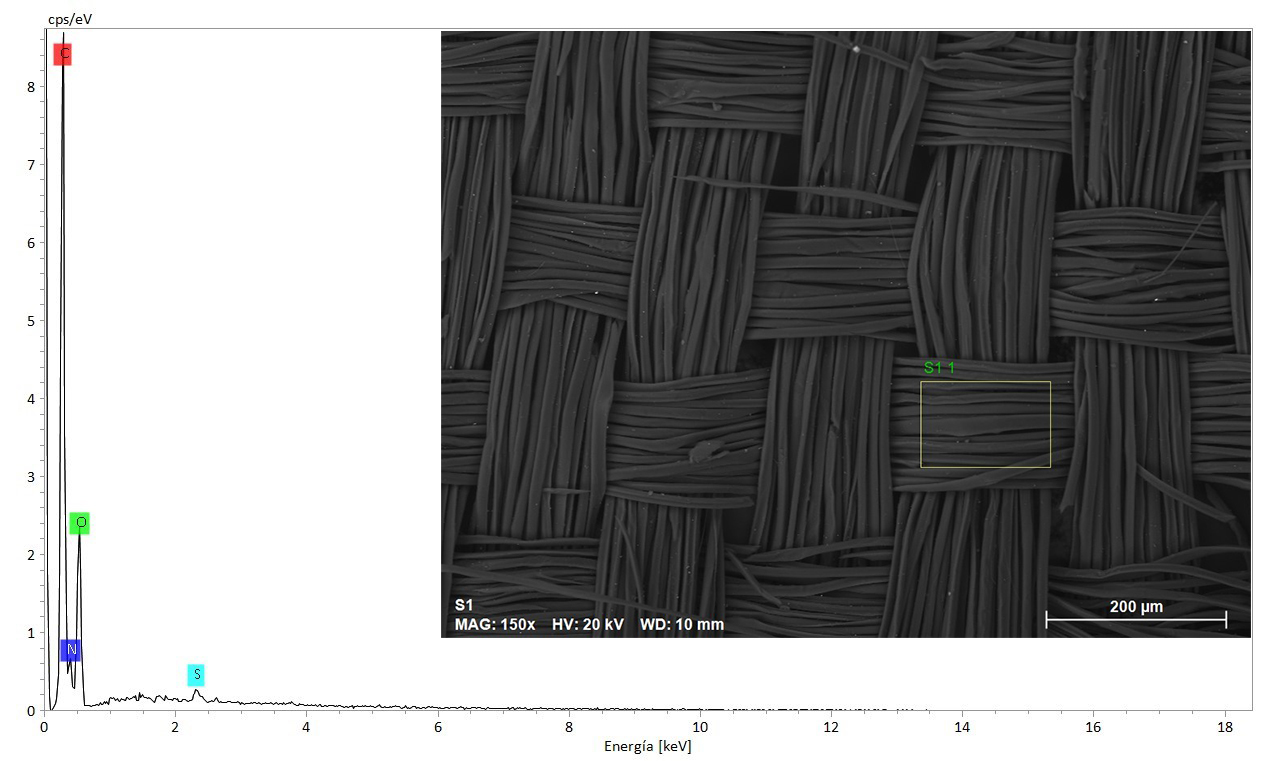

For the characterization of the materials, two samples were collected from the dress, one from an area of the shattered silk and another from the smock work. Both were studied and analyzed at the Institut Valenciá de Conservació, Restauració i Investigació (IVCR+i), in Spain, where microscopy techniques included Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) with a Bruker team Corporation XFlash® of an accelerating voltage 20 kV or an optical microscope Nikon ECLIPSE 80i with a Nikon DS-Fi1 camera with polarized light and UV illumination. The results gathered in both samples found silk to be the main component. Starting from the threads used for the construction of the smock work, the optical microscope identified two Z-ply silk threads dyed dark brown. This thread typology was often used for embroidery work as well as for decorating dresses with smock-work techniques. The results obtained from the pink silk were very surprising since the scientific analysis did not find any metal component that would have been linked to weighting processes or even with known mordant processes. It is possible to conclude from the microanalyses carried out with EDX that only oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulphur were registered—but not other components such as silicon, tin, and phosphorus, typically associated with weighted silks (Fig. 11),43 or alum, generally linked with mordant processes—leading to the conclusion that the silk was not weighted nor mordanted.

The chemical element identified by EDX as sulphur could be contributing to the currently unstable condition. Previous studies have shown that a sulphur component has been mistakenly attributed to the main composition of the fibroin from silk, and very little is said about the possible traces that could have been left in silk from the bleaching process before the dyeing process was started.44 This initial process, referred to as degumming, was finished with the assistance of alkali baths with soaps and acid solutions in order to remove the natural color of the fiber.45 The addition of sulphuric acid into this solution gave the material a characteristic rustle effect, also known as scroop,46 which later contributed to many silks shattering (Fig. 11). Despite the very low concentrations of sulphur seen in the EDX spectra, it seems that this was the main source of its active degradation, which in combination with humidity would have encouraged the silk to shatter.47 The bleaching process also introduces alkaline bisulphites, sodium peroxide, sodium hydrogen sulphite, or other acids48 through a process known during the late nineteenth century as sulphur stoving. This process involved exposing the moistened silk to the fumes of burning sulphur (creating sulphur dioxide), which in contact with water converted into sulphurous acid.49 In theory, all of this should have been removed in subsequent washings, but often this was done incompletely, leaving residues of the agent in the material. Different studies have shown that the silks that were only submitted to bleaching processes have aged better than the ones subjected to the weighting process.50 However, the silks that were bleached showed a very sensitive reaction to both high temperatures and humidity, conditions often found during the steaming process of the dresses. This last method in combination with the residual components of sulphur presented on the fibres could have led to the degradation of the silk by hydrolysis.51 Equally, the absence of any other metal element link with the mordanting process of the fabric contradicted the way Liberty used to work with their fabrics. During a visit by Keren Protheroe and Anna Buruma in June 2023 to prepare for a Liberty book, they noted the fashion house’s preferential use of mordant after dyeing their imported fabrics in England to fix the natural colorants into the fabric.52 This was corroborated in the early catalogues, which document Liberty’s use of vegetable dyes formulated by Thomas Wardle, for hand dyeing their imported silks. Wardle and William Morris later redeveloped the vegetable dyes together before Morris left the company. Wardle continued developing natural dyes with Arthur Liberty, creating the Liberty Art Colours at least till 1904, when the British house owned the department.53 Wardle studied synthetic dyes as well; however, his energies at Liberty were focused on expanding their valuable knowledge of vegetable dyes.54 Despite not conducting dye analysis, the absence of any mordant element would discount the use of any natural dye since the only direct dye known at the time was done with the assistance of synthetic dyes, which would directly contradict the way Liberty was working at the time.

Conservation approach

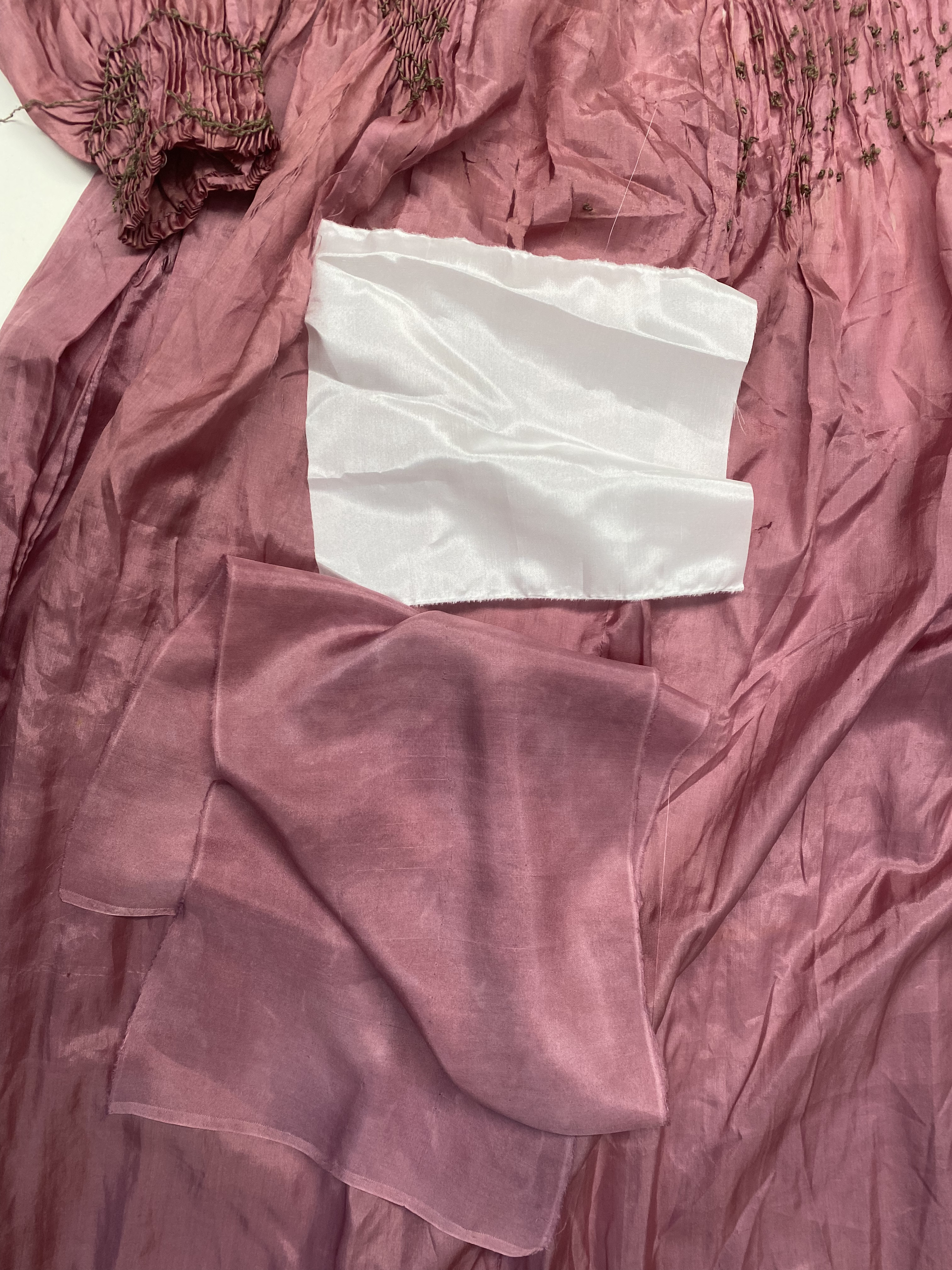

Since there are not many surviving samples in museum collections of reform dresses inspired by Liberty, a conservation plan was necessary. The dress is a surviving representative of social change at the end of the nineteenth century for women’s rights and reflects a very particular history in Indonesia and the cultural exchange between the Western and Eastern worlds. It also reflects a particular attachment with the wearer, since its current condition captures the moment when the dress was transformed by Anne after her child was born (1908), and the way it was reused after her body had changed. However, the very damaged silk and the missing areas of the original design prevent the dress from being exhibited with valuable context and additional information. Equally, considering the work Anne did during the transformation, it seems to us very important to tell how the dress once was before the modification happened (1902–3), showing the influence Liberty had on the manufacture of the dress. Consequently, different options were discussed. First was the recovery of the missing smock work, which is a complicated task since the silk was in poor condition and could not adequately hold the new smock work in place. The interior lining was also incomplete, missing half of its original structure from the time the smock work was removed to accommodate Anne’s pregnancy (Fig. 13).

The conservation approach taken for weighted silks in fashion collections has generated controversy since treatment options for rescuing the material have ranged from reproduction and substitution to intervention.55 All the stitching options were rejected since the silk broke very easily any time it was manipulated. With few viable options, the choice was made to utilize a combination of adhesive and stitching as the best consolidation option. This way of working has been already reported by colleagues in other museums in order to take advantage of the very thin adhesive bond between the new conservation support and the original silk, which tends to be reversible due to the very low adhesive concentration.56 Taking this approach as a treatment option, different mock-ups were made with different habutai silk thicknesses in combination with crepeline supports, all of them dyed in matching colors with CIBA© Lanaset dyes. The silk habutai added strength to the consolidation process while the crepeline helped introduce the chosen adhesive to the damaged textile and create an appropriate adhesive bond. From the adhesive choices, acrylic base adhesives were selected, such as Lascaux 360 HV/498, Evacon-R™, and Mowilith DM5/DMC2,57 due to their easy application and their nontoxic characteristics. For testing purposes, all were cast on the crepeline support and examined closely for the most desirable performance. Evacon-R™ performed the best since it avoided introducing rigidity or color changes to the material. The option of treating all of the silk was completely discarded from the beginning since that would have included removing some of the remaining original smock threads.

The next step was to study the remaining smock work, the most visual aspect of the dress. Different mock-ups were constructed with new smock threads, selected to be as similar to the original threads as possible. The selected thread was slightly thicker and lighter but very similar in twist, making very clear the differences between the original thread and the new addition without introducing new tensions. The smock work was finally constructed following the original stitches of the dress with step wave stitch and cable stitch, restoring the original design (Figs. 13, 15).

The interior of the dress was also discussed during the conservation treatment plan. The mutilated lining with the brown staining—linked with Anne Beatrix Darlang-Hoogesteger’s pregnancy and breastfeeding—as well as some remaining original length before it was cut at the left side, serve as historical references to maternal dress modifications that were not found during this research in any other dresses in museum collections from the early twentieth century. Using the original remnants as a reference, the reconstruction of the interior lining was started, drawing the full construction first over a piece of uncoated polyethylene terephthalate (also known under the brand Melinex©) and corrected on paper before it was translated onto the fabric. For the reconstruction, a similar material was chosen, drawing a very thin batiste cotton from our conservation fabric archive. Before it was used, it was pre-washed with a nonionic surfactant and dyed with Solophenyl© dyes matching the original color of the lining. Both pieces were sewn together with two-yarn silk threads that were fixed into the new support by the addition of running and couching stitches. Finally, the entire structure was protected with a very fine nylon net that was overlapped to avoid exposing the raw edges. The option to recover the waistband was totally discarded since the silk was very fragile and the addition would have compromised the ability to display the dress since the silk would be required to stretch as it was put on a mannequin. The recovery of the lining also helped support the new smock work at the front, since the original stitches that hold both supports in place were also removed after the pregnancy (Fig. 15).

Conclusions

The research presented in this article has shown the benefits of working from a multidisciplinary point of view where science, history, and conservation are used together to study and treat a unique dress. Inspired by the fashionable Liberty dresses, the wearer chose a lightweight silk rational dress that gave her freedom from the very strict Victorian fashion codes and comfort in Indonesia’s tropical weather.

The material research provided new insights into weighted silks and the possible degradation process linked to the bleaching known as sulphur stoving, a traditional method described in the literature of the early twentieth-century silk producers,58 making this dress one of the few surviving examples identified in the current literature*.* Collaboration between different institutions and textile conservators who had treated similar pieces was especially important in choosing the right conservation treatment approach for recovering the missing areas without causing additional damage to the silk.

This research also identified the historical importance of incomplete areas of this dress since they document the wearer’s modifications to accommodate her pregnant and breastfeeding body. Finally, the recovery of the original design during the conservation treatment has shown how the dress once was before this necessary modification, highlighting very close similarities with Liberty creations and the so-called reform dress (Fig. 16).

Other aspects have been left open for future research, such as the possibility of prefabricated body linings that were sent by pre-order to local fashion houses before the dresses were put together, shortening the fitting process. This research on the use of prefabrication linings is limited at best, but the KMDH collection holds different examples of dresses with linings like this one, and we hope to explore this topic in greater detail in future research. Finally, the absence of any mordant element confirmed that Liberty, which exclusively used vegetable dyes requiring mordant agents for fixing the color into the fabric, could not have been the manufacturer. However, limited published research into Liberty’s fabrics presents an opportunity to delve into Liberty archives and understand if the British fashion house truly worked exclusively with natural dyes or if the focus on natural methods was a marketing strategy following the Arts & Crafts movement.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all those who made this project possible, including Doede Hardeman, head of collections, Kunstmuseum Den Haag; Bernice Morris, textile conservator, Philadelphia Museum of Art; Dr. Naomi Luxford, conservation scientist, English Heritage Centre; Dr. Paul Garside, Kelvin Centre for Conservation and Cultural Heritage Research, University of Glasgow; Keren Protheroe, senior archivist, Liberty Fabrics; Anna Buruma, archivist, St Martin´s School of Art; Ilaria de Palma, head, Costume Conservation Department, Palazzo Morando; and Gemma Contreras Zamorano, director, Institut Valenciá de Conservació, Restauració i Investigacio. Finally, we would like to make a special dedication to Noah Rodriguez Pozo, who was born at the moment this research was completed, as well as to César Rodríguez Salinas’s partner, Iciar Pozo Julian, who was tremendously supportive of this project.

Author Bios

César Rodríguez Salinas holds an MSc in analytical techniques applied to the preservation of cultural heritage and is a specialist in the conservation and restoration of textiles. He is a fashion and textile conservator at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag in the Netherlands.

Madelief Hohé holds an MA in art history and is a fashion and costume curator at Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Dr. Livio Ferrazza has a Ph.D. in chemistry and is a conservator scientist at the Institut Valencià de Conservació, Restauració i Investigació (IVCR+i), in Spain.

Bibliography

Benington, Jonathan, and Sophia Wilson, eds. Simply Stunning: The Pre-Raphaelite Art of Dressing. Exh. cat. Cheltenham: Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museums, 1996.

Calvert, Robyne Erica. “Fashioning the Artist: Artistic Dress in Victorian Britain, 1848–1900.” PhD diss., University of Glasgow, 2012.

Cunningham, Patricia A. Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850–1920: Politics, Health and Art Kent: Kent State University Press, 2003.

Den Dekker, Annemarie. Rijk gekleed: Van doopjurk tot baljapon, 1750–1914. Edited by Amsterdams Historisch Museum. Amsterdam: Thoth, 2005.

Evans, Caroline. The Mechanical Smile: Modernism and the First Fashion Shows in France and America, 1900–1929. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

Garside, Paul. “Investigations of Analytical Techniques for the Characterisation of Natural Textile Fibres Towards Informed Conservation.” PhD diss., University of Southampton, 2002.

⸻, Graham A. Mills, James R. Smith, and Paul Wyeth. “An Investigation of Weighted and Degraded Silks by Complementary Microscopy Techniques.” ePreservation Science 11 (2014): 15–21.

⸻, Paul Wyeth, and Xiaomei Zhang. “Understanding the Ageing Behaviour of Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Tin‐weighted Silks.” Journal of the Institute of Conservation 33, no. 2 (2010): 179–93.

Hacke, Marei. “Weighted Silk: History, Analysis and Conservation.” Studies in Conservation 53 (2008): 3–15.

Higgins, Sydney Herbert. Historic Bleaching. London: Longs, Green, 1924.

Hohé, Madelief. “Esthetisch en elegant: Art nouveau en reformkleding.” In Art Nouveau in Nederland, by Jan de Bruijn, Frouke van Dijke, and Madelief Hohé, 144–63. Exh. cat., Kunstmuseum Den Haag. Zwolle: WBooks, 2018.

⸻. Global Wardrobe. Edited by Kunstmuseum Den Haag. Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 2022.

⸻. “Paul Poiret: Mode door Le Magnifique.” In: Art Deco, 184–203. Exh. cat., Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. Zwolle: WBooks, 2017.

⸻. Mode [Loves] Kunst. Exh.cat., Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 2011.

⸻, and Daan van Dartel. “Mode, musea en dekolonisering.” In Global Wardrobe, edited by Kunstmuseum Den Haag, 80–88. Zwolle: Waanders uitgevers, 2022.

Luxford, Naomi. "Reducing the Risk of Open Display: Optimising the Preventive Conservation of Historic Silks. PhD diss., University of Southampton, 2009.

Meij, Ietse. “Kunstenaars en vrouwenkleding omstreeks 1900.” Kunstlicht, no. 8 (Winter 1982/83): 24–33.

⸻. “Mode en Reform.” In Den Haag rond 1900: Een bloeiend kunstleven, by Titus M. Eliëns, M. Josephus Jitta, and Ietse Meij, 40–53. Exh. cat., Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. Blaricum: Museum Het Paleis/V+K, 1998.

Meijer, Suzan. “Bonding issues? Adhesive Treatments Past and Present in the Rijksmuseum.” ICOM Committee for Conservation preprints. 17th Triennial Meeting, Melbourne. Paris: ICOM 2014.

⸻, and Marjolein Koek. “Learning from a Treatment that Did Not Go As Planned: The Use of an Adhesive Support Technique on an 1860s Dress.” In The Textile Specialty Group Postprints, American Institute for Conservation 45th Annual Meeting (Chicago, 2017), 111–24.

Odabasi, Sanem. “Repair of Fashion Objects: An Interview with Sarah Scaturro.” Fashion Practice 15, no. 1 (2021): 1–15.

Parry, Linda. Textiles of the Arts & Crafts Movement. London: Thames & Hudson, 1988.

Rodríguez Salinas, César, and Livio Ferrazza. “Estudio científico y tratamiento de conservación de un vestido Chino Jifu de finales del siglo XIX.” Ge-Conservación, no. 20 (2021): 205–18.

Schnitger, Carin, and Inge Goldhorn. Reformkleding in Nederland. Utrecht: Centraal Museum Utrecht, 1984.

Squire, Geoffrey. “Clothed in Our Right Minds’: Some Wearers of Aesthetic Dress.” In Simply Stunning: The Pre-Raphaelite Art of Dressing, edited by Jonathan Benington and Sophia Wilson. Exh. cat. Cheltenham: Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museums, 1996.

Thompson, Eliza B. Silk. Merchandise Manual Series. New York: Ronald Press, 1922.

Timmer, Petra. Metz & Co: De creatieve jaren. Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010, 1995.

Vedrenne, Laura Garcia. “Drawing a Fine Line: Ethical Ramifications in Replacing the Shattered Silk Linings on Two Callot Soeurs Dresses.” Outside Influences, 13th American Textile Conservation Conference (online, 2021), postprint proceedings, 221–42.

Veenendaal, Jan. Asian Art and Dutch Taste. Edited by Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. Zwolle: Waanders uitgevers, 2014.

Wilson, Sophia. “Away with the Corsets, on with the Shifts.” In Simply Stunning: The Pre-Raphaelite Art of Dressing, edited by Jonathan Benington and Sophia Wilson, 20–27. Cheltenham: Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museums, 1996.

Notes

-

This was possible to confirm by the notice in the Dutch newspaper Rotterdams Nieuwsblad, 19 January 1909, where the birth of Anne Marie Christien was mentioned. ↩︎

-

Madelief Hohé, *Mode *[Loves] Kunst, exh. cat., Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 2011); Madelief Hohé, “Esthetisch en elegant: Art nouveau en reformkleding in Nederland,” in Art Nouveau in Nederland, by Jan de Bruijn, Frouke van Dijke, and Madelief Hohé, exh. cat., Kunstmuseum Den Haag (Zwolle: WBooks, 2018), 144–63. ↩︎

-

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1995-82-1; Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986.115.5 Since the collar and insert of the KMDH dress differ so greatly from the one in Philadelphia, it could be a later alteration. ↩︎

-

Geoffrey Squire, “‘Clothed in Our Right Minds’: Some Wearers of Aesthetic Dress,” in Simply Stunning: The Pre-Raphaelite Art of Dressing, ed. Jonathan Benington and Sophia Wilson, exh. cat. (Cheltenham: Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museums, 1996), 91. ↩︎

-

The information was shared by colleagues at the KDMH, Tirza Westland and Jacoba de Jonge, based on the discovery of different linings in our collection. ↩︎

-

Petra Timmer, Metz & Co: De creatieve jaren (Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010, 1995), 22; Carin Schnitger and Inge Goldhorn, Reformkleding in Nederland (Utrecht: Centraal Museum Utrecht, 1984) 46. ↩︎

-

Hohé, Mode [Loves] Kunst, 77. ↩︎

-

Ietse Meij, “Mode en Reform,” in Den Haag rond 1900: Een bloeiend kunstleven, by Titus M. Eliëns, M. Josephus Jitta, and Ietse Meij, exh. cat., Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (Blaricum: Museum Het Paleis/V+K, 1998): 40–53. ↩︎

-

Amsterdam Museum, acc. nos. KA 20031 and KA 20032. ↩︎

-

Robyne Erica Calvert, “Fashioning the Artist: Artistic Dress in Victorian Britain, 1848–1900” (PhD diss., University of Glasgow, 2012), 28, 152. ↩︎

-

Jonathan Benington, Simply Stunning: The Pre-Raphaelite Art of Dressing (Cheltenham: Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museums, 1996), 4. ↩︎

-

Schnitger and Goldhorn, Reformkleding in Nederland, 31–34. ↩︎

-

Calvert, Fashioning the Artist, 27. ↩︎

-

Patricia A. Cunningham, Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850–1920: Politics, Health and Art (Kent: Kent State University Press, 2003), 69. ↩︎

-

Cunningham, 24. ↩︎

-

See, for example, the third issue of Aglaia: The Journal of the Healthy and Artistic Dress Union, published in the Autumn of 1894 by the University of Southampton: https://archive.org/details/krl00000763/mode/2up. ↩︎

-

Schnitger and Goldhorn, Reformkleding in Nederland, 8–12. ↩︎

-

Schnitger and Goldhorn, 1, 4–5. ↩︎

-

Schnitger and Goldhorn, 51. ↩︎

-

Schnitger and Goldhor, 18. ↩︎

-

Hohé, “Esthetisch en elegant,” 66. ↩︎

-

Schnitger and Goldhorn, Reformkleding in Nederland, 17. ↩︎

-

Calvert, Fashioning the Artist, 190. ↩︎

-

Several authors have pointed out the transition period before the corset was totally forgotten. See Schnitger and Goldhorn, Reformkleding in Nederland, 5; and Annemarie Den Dekker, Rijk gekleed: Van doopjurk tot baljapon, 1750–1914, ed. Amsterdams Historisch Museum (Amsterdam: Thoth, 2005): 88. This is the case of the watercolour from Antoon Molkenboer titled Gedurende de pauze in de wandelgangen van het Concertgebouw (1903), which illustrates various women at the concert hall in Amsterdam, looking at each other’s dresses. ↩︎

-

Schnitger and Goldhorn, Reformkleding in Nederland, 39. ↩︎

-

Madelief Hohé, “Paul Poiret: Mode door Le Magnifique,” in Art Deco, exh. cat., Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (Zwolle: Waanders & De Kunst 2017), 192; Caroline Evans, The Mechanical Smile: Modernism and the First Fashion Shows in France and America, 1900–1929 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 204. ↩︎

-

From the beginning of the twentieth century, Dutch newspapers enthusiastically promoted her designs, including Maandblad in 1903, Arnhemse Courant (4 April 1902), and Nieuwe Tilburgsche Courant (May 24, 1902), just to mention a few. ↩︎

-

Schnitger and Goldhorn, Reformkleding in Nederland, 37. ↩︎

-

Liberty’s Art Fabrics, 1883, Westminster Public Libraries, acc. no. 788, doc. No. 29/1. Information provided by Keren Protheroe, senior archivist, Liberty Fabrics. Personal communication to the authors, 21 August 2023. ↩︎

-

Schnitger and Goldhorn, Reformkleding in Nederland, 84. ↩︎

-

See Victoria and Albert Museum, T.17-1985; and Fashion Institute of Technology, 2008.25.3. The smock work characteristic of different sketches by Greenaway may have inspired Liberty’s designs. See Kate Greenaway’s Almanack for 1893 ([London]: George Routledge & Sons, 1893). ↩︎

-

Sophia Wilson, “Away with the Corsets, on with the Shifts,” in Simply Stunning, 21. ↩︎

-

Calvert, Fashioning the Artist, 144. ↩︎

-

This was confirmed by Keren Protheroe, senior archivist, Liberty Fabrics, and by Anna Buruma, archivist, St Martin’s School of Art, Research consultancy in Kunstmuseum Den Haag archives (27/06/2023). ↩︎

-

See a Liberty dress sold by Augusta Auctions, 2017, lot number 239, accessed 24 March 2022, https://augusta-auction.com/auction?view=lot&id=17672&auction_file_id=46. For a dress labelled as Liberty and available online at Etsy, see https://www.etsy.com/nl/listing/831714215/19e-eeuwse-liberty-of-london-silk?ref=shop_home_active_3&frs=1&cns=1, accessed 25 March 2022. The auction house Doyle sold in 2002 (lot 78) a similar dress with a Liberty label on the inside, with similar smocking at the bodice yoke, sleeves, and waistband; https://www.pinterest.com/pin/565131453254192869/sent/?invite_code=9956fa132c7c4af5b8c2226afa03fccd&sfo=1. The cut of the collar was similar in all three dresses, but only the dress from Augusta showed Liberty’s characteristic embroidered flowers and the fabric-covered buttons at the back. ↩︎

-

Anna lived in Indonesia with her husband for at least thirty-six years. Her wardrobe contained all sort of garments, from the traditional items that Dutch women in Indonesia wore as informal wear, such as kebaja and sarong, to traditional men’s attire, probably worn by her husband. The distinction between the garments of the Indonesian women, who worked for the European families, and the European women was indicated by colour of the kebaja, with darker colours for Indonesian women; in addition, European women wore sarong with a mix of European and traditional Indonesian motives, as opposite to the more traditional Indonesian sarongs worn by Indonesian people. Jan Veenendaal, Asian Art and Dutch Taste, ed. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (Zwolle: Waanders uitgevers, 2014), 192. Both the white baadje and colorful batik slaapbroek (“sleeping pants”) were men’s garments made of batik and worn at home. The baadje was a cotton jacket with a Chinese closure, while the slaapbroek were trousers with loose legs but fitted at the waist. Madelief Hohé, Global Wardrobe, ed. Kunstmuseum Den Haag (Waanders uitgevers: Zwolle, 2022), 23–24. ↩︎

-

Madelief Hohé and Daan van Dartel, “Mode, musea en dekolonisering,” in Global Wardrobe, 80–88. ↩︎

-

Veenendaal, Asian Art and Dutch Taste, 191. ↩︎

-

All of the biographical information on Anne in this paragraph was sourced from local newspapers via delpher.nl and documents in the museum’s collection. ↩︎

-

The moment of the death of Frederik Filip Franciscus Darlang was widely publicized by the Dutch press at the time, including in De Locomotief, 8 June 1909. ↩︎

-

Calvert, Fashioning the Artist, 37, 122, 133. ↩︎

-

For cable stitch, see https://youtu.be/i7zdmCfB4IQ; for step-weave stitch, https://youtu.be/JWRB4XFdrv4 (accessed 12 August 2023). ↩︎

-

César Rodríguez Salinas and Livio Ferrazza, “Estudio científico y tratamiento de conservación de un vestido Chino Jifu de finales del siglo XIX,” Ge-Conservación, no. 20 (2021): 212. Dr. Naomi Luxford confirmed: “If the silk has been weighted with tin (or any other elements), then the tin (or other elements) would be present in the EDX, [and] any other processing wouldn’t remove the weighting as it binds inside the fibers.” Personal communication to the authors, 28 April 2022. ↩︎

-

Naomi Luxford, previously delved into this subject in her Ph.D. dissertation titled "Reducing the Risk of Open Display: Optimizing the Preventive Conservation of Historic Silks (Ph.D. diss., University of Southampton, 2009), 84–85. ↩︎

-

Paul Garside, "Investigations of Analytical Techniques for the Characterisation of Natural Textile Fibers Towards Informed Conservation (PhD diss., University of Southampton, 2002), 186. ↩︎

-

Paul Garside, Graham A. Mills, James R. Smith, and Paul Wyeth, “An Investigation of Weighted and Degraded Silks by Complementary Microscopy Techniques,” ePreservation Science 11 (2014): 16. ↩︎

-

Luxford, “Reducing the Risk,” 56. [Confirmed by Dr. Paul Garside in a personal communication to the authors, 28 April 2022. ↩︎

-

Garside, “Investigations of Analytical Techniques,” 186. ↩︎

-

Garside et al., "Investigation of Weighted, 16. ↩︎

-

Paul Garside, Paul Wyeth, and Xiaomei Zhang, “Understanding the Ageing Behaviour of Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Tin‐weighted silks,” Journal of the Institute of Conservation 33, no. 2 (2010): 189; Garside et al., “Investigation of Weighted,” 18. ↩︎

-

Garside et al., “Investigation of Weighted,” 191. ↩︎

-

Liberty also promoted its business in the United States, and one American department store manual stated that the British fashion house only dyed its silks with vegetable dyes. See Eliza B. Thompson, Silk, Merchandise Manual Series (New York: Ronald Press, 1922), 179. ↩︎

-

Linda Parry, Textiles of the Arts & Crafts Movement (London: Thames & Hudson, 1988), 102, 133–34. ↩︎

-

Parry, 152. ↩︎

-

Sanem Odabasi, “Repair of Fashion Objects: An Interview with Sarah Scaturro,” Fashion Practice 15, no. 1 (2021): 9–10; Laura Garcia Vedrenne, “Drawing a Fine Line: Ethical Ramifications in Replacing the Shattered Silk Linings on Two Callot Soeurs Dresses,” in “Outside Influences,” 13th American Textile Conservation Conference (online, 2021), postprint proceedings, 221–42. ↩︎

-

Suzan Meijer, “Bonding Issues? Adhesive Treatments Past and Present in the Rijksmuseum,” ICOM Committee for Conservation preprints, 17th Triennial Meeting, Melbourne (Paris: ICOM, 2014), 4; Suzan Meijer and Marjolein Koek, “Learning from a Treatment that Did Not Go As Planned: The Use of an Adhesive Support Technique on an 1860s Dress,” in The Textile Specialty Group Postprints, American Institute for Conservation 45th Annual Meeting (Chicago, 2017), 111-24. Thanks to the generosity of textile conservator Bernice Morris from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, it was discovered that their Liberty dress (catalogued as “Woman’s dress,” 1995-82-1) was submitted to a conservation treatment in 2015, at which time the very fine damaged silk was consolidated by an adhesive bond in combination with stitching techniques. Personal communication to the authors, 3 December 2021. The use of adhesive in textile conservation is continuously studied and controversial. For her dissertation, Erin Thompson, a master’s student in the Department of Conservation at the University of Lincoln, is studying the use and characteristics of adhesive castings in textile conservation, as well as the decisions that lead to their use. Personal communication to the authors, 20 August 2023. ↩︎

-

All the adhesives were prepared in similar proportions of one part adhesive dissolved in four parts water. ↩︎

-

Sydney Herbert Higgins, Historic Bleaching (London: Longs, Green, 1924). ↩︎